Graft is a productive bundle of contradictions. The five young partners collaborate on every design even though they are now working out of Los Angeles, Berlin, and Beijing. In their 12 years of practice, they’ve progressed from temporary installations to varied buildings and on to master plans and major urban developments, while insisting that they tackle only the projects that inspire them. The bright colors and swooping lines of their exuberant hotels, restaurants, and commercial interiors carry over into an ambitious project to rebuild a devastated ward of New Orleans. Playful and serious, inventive and socially responsible, there seems no limit to the potential of Graft.

Graft is a productive bundle of contradictions. The five young partners collaborate on every design even though they are now working out of Los Angeles, Berlin, and Beijing. In their 12 years of practice, they’ve progressed from temporary installations to varied buildings and on to master plans and major urban developments, while insisting that they tackle only the projects that inspire them. The bright colors and swooping lines of their exuberant hotels, restaurants, and commercial interiors carry over into an ambitious project to rebuild a devastated ward of New Orleans. Playful and serious, inventive and socially responsible, there seems no limit to the potential of Graft.

The venture started by chance. Gregor Hoheisel, Lars Krückeberg, Wolfram Putz, and Thomas Willemeit studied architecture together at the Braunschweig Technical University in north Germany and cemented their friendship by forming an a capella jazz group. Like many Europeans, they found a new freedom in Los Angeles, where two of them completed their graduate studies and decided to establish an office there. They named it Graft to express the idea of a robust crossbreed, analogous to grafting a shoot onto a genetically different host. The partnership began as a commune, sharing a house and resolving, as Willemeit recalls, "to do what we love, and that way we can’t fail."

"We started out in Hollywood and did a lot of temporary stage sets for art and film, and that showed us what we could achieve with different materials and technologies," says Krückeberg. "We are all driven by great stories, and we believe architecture can be storyboarded like a movie." That attitude drew the interest of Brad Pitt, an actor who easily might have become an architect. He worked with them on a house, a studio, and plans for a visionary resort in the desert. Graft broadened its scope by designing innovative installations for SITE Sante Fe, an interactive children’s exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Moonraker, a futuristic environment for Volkswagen near Los Angeles. The designers opened offices in Berlin in 2001 and Beijing in 2003, and they thrived on the challenge of engaging different cultures. "When we went back to Germany, we were cowboys, the easy-going sunshine dudes from Hollywood," says Krückeberg. "Americans see us as serious Germans, punctual and precise, and in China we are sophisticated Westerners grafting ourselves onto local sensibilities."

Hoheisel has settled in Beijing, but his colleagues constantly move around, staying in touch by e-mail and conference calls. Twice a year they get together for a planning session. "There’s a salad bowl of ideas to begin with, and the partners push, stir things up, and ask questions," explains Putz. "It’s almost a Dadaistic effort where you exchange half-finished paintings—a good business model for content development. Always, there’s a project leader, who stays in place until the job is completed." Willemeit likens the consensual approach to a jam session, in which each member of the group plays solo in turn, improvising on a theme. "It’s a strategy to provoke the unexpected—in contrast to a hierarchical office, which tends to generate predictable solutions," he says.

Hoheisel has settled in Beijing, but his colleagues constantly move around, staying in touch by e-mail and conference calls. Twice a year they get together for a planning session. "There’s a salad bowl of ideas to begin with, and the partners push, stir things up, and ask questions," explains Putz. "It’s almost a Dadaistic effort where you exchange half-finished paintings—a good business model for content development. Always, there’s a project leader, who stays in place until the job is completed." Willemeit likens the consensual approach to a jam session, in which each member of the group plays solo in turn, improvising on a theme. "It’s a strategy to provoke the unexpected—in contrast to a hierarchical office, which tends to generate predictable solutions," he says.

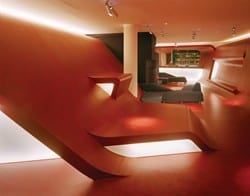

Hotels have proved fertile ground for Graft. One of its first major projects was the Q, located just off the Kurfurstendamm in the fashionable hub of West Berlin. In contrast to many design hotels, it is a seamless whole in which the same fluid forms are used consistently from entry to guestroom. Red linoleum flows over walls and floors, curving to accommodate shelves and wall benches, and stopping short of the ceiling. Within the 200-sq.-ft. guestrooms, the beds curve up to incorporate a tub and a slate-topped vanity, and a dark wood closet curves down to provide a desk top on the opposite wall, leaving space for an enclosed shower and toilet beside the entry. Thanks to this ingenious configuration and the crisp black and white palette, the tiny rooms have an air of spacious sophistication.

"In hotels you can crank up the volume because you live there for only a few days," says Willemeit. For Hoheisel, "hotels are like stage design—a refreshing place where guests can be someone else for a short time. But travelers also want to enjoy the unique experience of a specific place, so we try to infuse hotels with the local culture." He continues, "The Emperor in Beijing is very close to the Forbidden City so we used traditional Chinese colors for the interior and identified the rooms with graphic portraits of different emperors. We just finished the Iveria, a big hotel in Tiblisi, Georgia, which draws inspiration from cave dwellings and wine culture."

Alejandra Lillo, who grew up in Argentina, recently became the fifth partner and now heads the Los Angeles office. She was partner in charge on the W Hotel in lower Manhattan, Graft’s largest U.S. building to date, which is scheduled to open in April. Located immediately adjacent to the site of the World Trade Center, it enjoys fantastic views but has to contend with the somber memories that will always haunt Ground Zero. "We wanted to open up compressed spaces to vistas within and beyond by punching out as many openings as possible," says Lillo. "But we also wanted to give the W a touch of edginess and joie de vivre, and we came up with the concept of punk minimalism, imagining a guy in a business suit with a pink Mohawk walking through the financial district."

Alejandra Lillo, who grew up in Argentina, recently became the fifth partner and now heads the Los Angeles office. She was partner in charge on the W Hotel in lower Manhattan, Graft’s largest U.S. building to date, which is scheduled to open in April. Located immediately adjacent to the site of the World Trade Center, it enjoys fantastic views but has to contend with the somber memories that will always haunt Ground Zero. "We wanted to open up compressed spaces to vistas within and beyond by punching out as many openings as possible," says Lillo. "But we also wanted to give the W a touch of edginess and joie de vivre, and we came up with the concept of punk minimalism, imagining a guy in a business suit with a pink Mohawk walking through the financial district."

Restaurants provide an ideal canvas for Graft’s love of storytelling and fantasy. In Las Vegas, the firm designed Fix in the Bellagio Hotel as a glowing cave framed by milled slats of wood. Still more exotic was Gingko Bacchus, an upscale restaurant in Chengdu, the capital of China’s Sichuan province. "The design developed as a series of layers," explains Hoheisel. "We started with the concept of treating the blacked-out circulation area as a stream with the eight private dining rooms as boulders along one bank." Stainless-steel lines set into the black granite floor evoke rippling water, and this effect is echoed in the undulating wood ceiling.

The outer wall of Gingko Bacchus is lined with high-resolution photos that put a fresh spin on 17th-century Dutch still-life paintings. These images are set behind one-way mirrors, and the lighting is controlled by a timer on a 20-minute cycle. Details are highlighted and then slowly fade to darkness, allowing diners to catch their own reflections. In the private rooms, vegetables are abstracted in wallpapers that range from artichoke green to red chili. Layered over these patterns are reproductions of old-master paintings of Bacchus, the god of wine, printed onto laser-cut sheets of stainless steel, with nymphs frolicking across the ceiling.

The Berlin office has employed a similar strategy of escapism for dentists who seek to put their patients at ease. ‘The trick is to work against expectations," says Krückeberg. "Most dental clinics are white and smell of disinfectant. For one client, we created a playful environment with the look of sand dunes, the smell of espresso that the receptionist offers to each new arrival, and cherry wood burning in an open hearth. Excited by the success of this first venture down the street from the Q Hotel, a children’s dentist commissioned an equally joyful extravaganza from Graft. A blue wave links three levels of the narrow storefront and evokes the underwater fantasies of Jules Verne. "We take a holistic approach and try to appeal to all the senses," says Hoheisel. "Light is important, as are the smell, acoustics, and sense of touch as you move through the space. You can design a beautiful restaurant, but if you can’t enjoy a good conversation, you’ll hate it."

The Berlin office has employed a similar strategy of escapism for dentists who seek to put their patients at ease. ‘The trick is to work against expectations," says Krückeberg. "Most dental clinics are white and smell of disinfectant. For one client, we created a playful environment with the look of sand dunes, the smell of espresso that the receptionist offers to each new arrival, and cherry wood burning in an open hearth. Excited by the success of this first venture down the street from the Q Hotel, a children’s dentist commissioned an equally joyful extravaganza from Graft. A blue wave links three levels of the narrow storefront and evokes the underwater fantasies of Jules Verne. "We take a holistic approach and try to appeal to all the senses," says Hoheisel. "Light is important, as are the smell, acoustics, and sense of touch as you move through the space. You can design a beautiful restaurant, but if you can’t enjoy a good conversation, you’ll hate it."

Adaptive reuse also is an important part of Graft’s work. They transformed a ruined factory in the former East Berlin into a complex of live-work spaces, exploiting its position on a bend of the Spree river to create a magnet for young entrepreneurs. The entry lies beyond two courtyards and a huge freight elevator that was part of the factory serves as a mobile lobby. The original idea was to put a receptionist in this spacious room, but the requirement that every German workplace have natural light made that impossible. Instead, the designers installed comfortable seating and a bar with music, colored lights, and videos related to the floor being accessed. The journey takes at least a minute, and the elevator has an after-hours role as a party space. Another adaptive reuse project will soon take place in Moscow, where Graft triumphed over several other prestigious firms to win a competition for the Russian Jewish Museum, to be housed in a landmark building.

The pivotal project in Graft’s brief career may turn out to be Make it Right (MIR), an idealistic response to the devastation of Katrina and the failure of the authorities to protect or re-house the poorest residents of New Orleans. Brad Pitt, who loves the city and was angered by its neglect, asked Graft to help in building 150 model homes for residents of the Lower Ninth Ward who owned sites but couldn’t afford to return. "We designed two houses that would be sustainable, affordable, and architecturally appropriate, but we realized we should not try to do everything ourselves," says Krückeberg. The partners brought in William McDonough, a major authority on sustainability, and Cherokee Gives Back, a charity run by a company that cleans up contaminated sites. Together they selected 13 local, national, and international architects to design a single-family residence. In a second phase, eight architects designed two-family duplexes.

Each of the houses was developed in close consultation with residents, who then made their choice from the menu of possibilities. It was a learning experience on both sides. Architects who usually work with other professionals were closely scrutinized by people who had never imagined they could afford good design. "It was very different from air-dropping a spectacular project in Ordos or some other architectural zoo," says Hoheisel. "Here we were working face-to-face, and we realized that architects can change people’s lives." As Lillo observes, "The task of the designer is to take every obstacle and turn it on its head to spur an innovative solution. Everyone should share the benefits of sustainability. It was truly moving to meet an owner boasting of his $3 electrical bill, and a mother telling me that her children no longer suffer allergies since they moved into their MIR house."

House Leader Nancy Pelosi called MIR a role model for the nation. Graft has been fielding inquiries from other distressed communities, and it collected the data and put it in a book, Architecture in Times of Need. The firm also created Pink, an installation that was dreamed up by Pitt and erected on the MIR site for the five weeks following Thanksgiving 2008. Inexpensively constructed from sheets of recyclable fluorescent pink fabric, it comprised 150 house-like blocks in 12 different configurations to anticipate the diversity of designs that would be realized over the next three years. It focused public attention on the potential of MIR and triggered donations from individuals around the world.

About 20 MIR houses have been completed, and the rest should be in place by the end of 2011. All are LEED-Platinum certified, making this the greenest community in the United States. Beyond its social utility, this community points the way forward for every architect and designer. As Krückeberg explains, "We can reclaim territory that has been taken away by developers and specialists. Think global; act local." As an example of this inclusive approach, Graft currently is developing a sustainable electrical power generator for African villagers that could dramatically improve their health and communications.

Gathered together for a creative retreat, the partners reflect on how far they’ve come in 12 years. "We need to be flexible in a way our parents were not," says Krückeberg. "If you don’t move around, you won’t have a job." The 40-something founders of Graft share ideas, work until 3 a.m. when they need to, and fly around the world without a second thought. "We are hosts and guests in every location, and that keeps you off balance and makes you think," Willemeit cuts in. "We don’t want to specialize; we’d rather try everything."