Power Couple

Idris Khan and Annie Morris use art to heal

When it came to their relationship, Idris Khan and Annie Morris fell fast and hard. In fact, they were engaged within five months of being set up by a mutual friend. Artistically speaking, however, they followed different paths. Morris grew up around art, her mother working in theater. Khan, meanwhile, the son of a surgeon and a nurse, wanted to be an athlete before he discovered his love of photos. Today, in the studio they share in London, she focuses on sculpture, as well as tapestry and painting, while he primarily works in photography.

But the couple’s world was rocked when they had a stillborn child in 2011. They both turned to their work to heal. Using their creative outlets to deal with such a tragedy was cathartic, to say the least. “It is a privilege to be an artist,” Morris says. Khan created stamp paintings of literary works, including the Quran (his father is from Pakistan) layering them with gesso paints for a specific effect on the words. Morris crafted the Stack series from plaster, sand, and cast bronze, with the circular shapes inspired by her pregnancy and representing fragility and power. Today, the couple has two children and recently displayed their work in an exhibition in India at a show called Re-Imaginings. When it comes to their art, Khan says, they are “always pushing the next idea.”

Going Strong

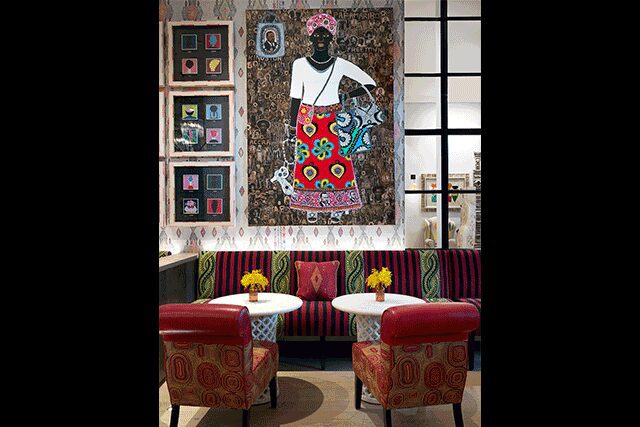

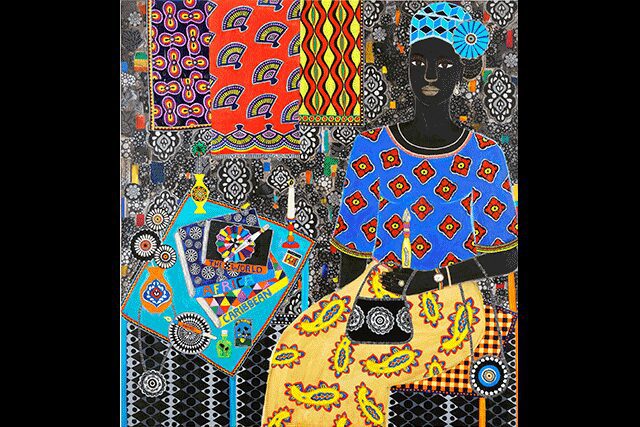

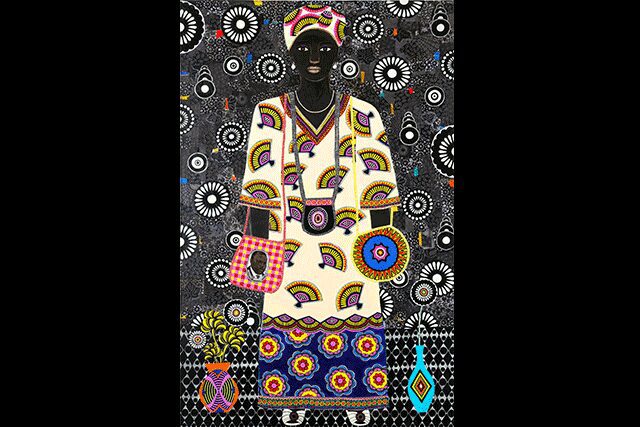

Carla Kranendonk explores female power

As a child, contemporary artist Carla Kranendonk was always drawing and painting, leading her to study at top art schools, including Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. But it was “a love affair with a boy from Surinam, South America,” now her husband, that inspired her signature style using acrylic paint on canvas and combining it with photocopies of African fabrics, yarn, glue, and cotton. Today, her work can be seen as “a tribute to the beauty, pride, tragedy, strength, and humor of the African and Afro-American people.” Her pieces celebrate women as powerful beings. Imane, for instance, depicts a reclining lady in bold colors and prints, while Khoudia “tells a story of a successful Senegalese independent woman” in traditional African garb who is resting in her garden hammock at night. Ultimately, “I want to create a lively, colorful world [with] positive vibes,” she says.

Fruit of the Loom

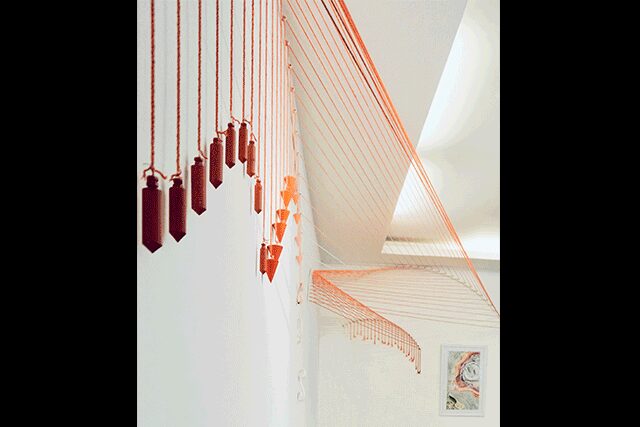

Hermione Skye defies expectations

Kit Kemp first came across Hermione Skye’s woven installations at Skye’s degree show at the Chelsea College of Art. Coining it the Loom, she commissioned the piece for the lobby of the Whitby Hotel in New York. A year later, Skye launched Wakimukūdō, her Helsinki-based studio that specializes in creating woven installations for a variety of hospitality projects with a core philosophy to “breathe life into the abandoned,” she says. “The crumbling, decaying, and rusting qualities of objects and buildings speak to my heart, they soothe my soul. [It’s] subconsciously relaxing—cracks and decay speak the truth.” Her latest project is an outdoor café in Jakarta, where white curtains surround the space “to capture the presence of the wind,” while the recently opened rooftop restaurant Ulana Gastronomia, also in Jakarta, features three of her signature installation, Looms, including one in a pastel peach that hangs over lichen green sofas.

Picture Perfect

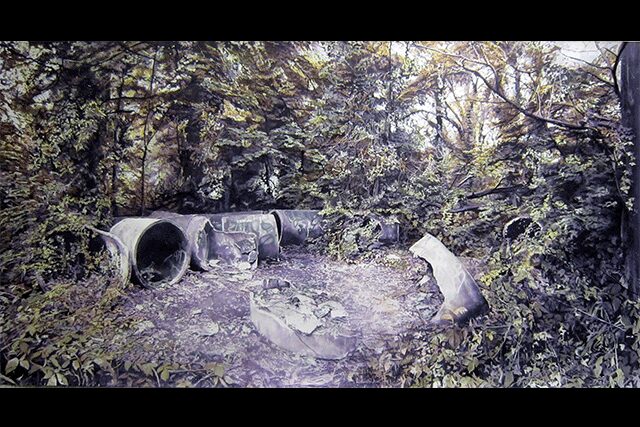

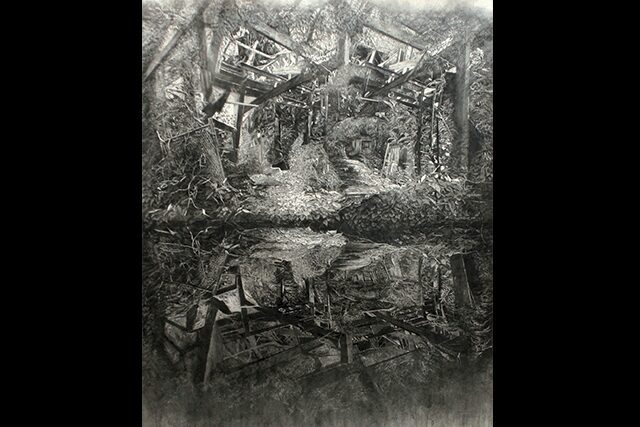

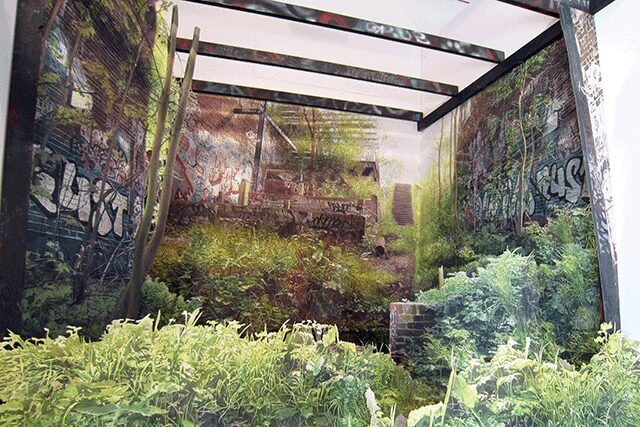

Juliette Losq finds beauty in decay

With master’s degrees in both art history and fine art from Cambridge University and the Royal Academy of Arts, it is no surprise that Juliette Losq was awarded the prestigious Jerwood Drawing Prize, cementing her status as an artist on the rise. Her detailed works of art depict the beauty of nature against the wrath of decay, ultimately creating intrigue with overlapping layers of ink and watercolor. “I draw from sites of contemporary ruination such as old boatyards, the remnants of factories, and disused railway lines,” she says, elevating them “to the status of grand history paintings, and at the same time, preserving these transient and neglected spaces.” Consider Proscenium, for which she won the John Ruskin Prize. The large-scale, immersive installation explores “the invisible boundary between the audience and the stage world” with “layered paper peepshows,” says Losq. The piece recreates a real location “for people who may never go there,” she says. “It allows the viewer a space to explore and project their imagination,” while showcasing nature’s resilience.