V. Mitch McEwen was already acquainted with fellow architectural designer Amina Blacksher, an adjunct assistant professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, when she got a chance to see Blacksher’s process up close. “The world of architecture is so small, and then the world of Black designers within it is even smaller. We could fit at one large cocktail party,” McEwen says. It was 2019, when McEwen was leading a conference at the Princeton University School of Architecture where she’s an assistant professor, that Blacksher unveiled Robot Double Dutch, a proposal investigating an analog and digital exchange. Afterwards, the two solo practitioners shared ideas and techniques, and eventually decided to join forces to create New York-based design practice Atelier Office.

V. Mitch McEwen

Launched last year, the practice fuses McEwen and Blacksher’s design and research expertise, exploring “machines in ways they’re not typically used or even designed for,” explains Blacksher. “Everything we do is architecture, whether it’s a prototype that involves teaching machines to recognize the precision of rhythm or designing a virtual world. How can we translate this into built work that doesn’t compromise any of our sky’s-the-limit way of thinking, but materializes it into something that can be produced?”

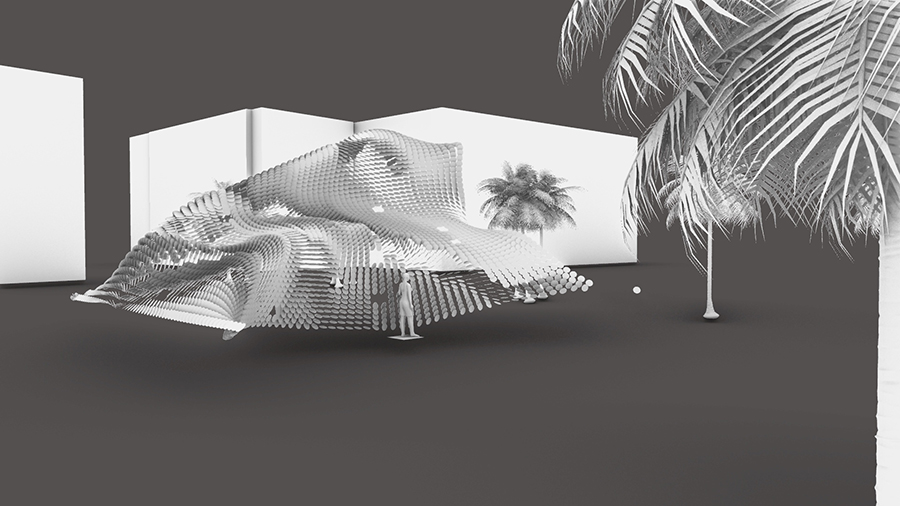

Among Atelier Office’s projects is Sparkle, an installation that was a finalist to be constructed for the Miami Design District that melds metal disks, solar cells, and LEDs. Resembling sequins, it winds through courtyards and passageways and captures the energy of the city’s queer community. Blacksher and McEwen also developed a multi-site concept and phasing strategy for Camden Repertory Theater, a nonprofit Black institution “that has been delivering culture to one of the poorest cities in New Jersey for over a decade. We want to show what’s behind the scenes—that it really is thinking from the grassroots up,” explains McEwen.

A rendering of Sparkle, Atelier Office’s metal and light installation celebrating queer culture in the Miami Design District

Prior to establishing Atelier Office, McEwen was commissioned to participate in Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, the recent exhibition at MoMA in New York. In collaboration with artist Kristina Kay Robinson, she imagined “an alternative version of New Orleans” and its architecture if the 1811 German Coast Uprising—the largest rebellion against U.S. plantation slavery—had been successful.

Neither Blacksher nor McEwen set out to become architects. Blacksher, who cut her teeth at BIG, Ennead Architects, and G TECTS, believes it was the Ithaca, New York landscape she grew up surrounded by that ignited her passion. When she was 6, she was caught by the undercurrent of a waterfall and was “close to going over a 100-foot drop. That is relevant for me not only visually, being struck by the forest, lakes, and gorges, but that dynamic forces are just as much a part of design as what we do see. I became interested in form as a continuum of movement,” she recalls.

Amina Blackher

McEwen, who worked in finance in Silicon Valley before plunging into architecture and theory in grad school, was raised in Washington, DC, where federal buildings like the one for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development crafted by Marcel Breuer made an impression. It was only during her undergrad studies at Harvard, when she was taking painting classes in the Le Corbusier-designed Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, that she “started to understand that there were architects behind these buildings, and there is a reason that certain structures can change the city around them.” Blacksher and McEwen are in the midst of doing the same.

This article originally appeared in HD’s June/July 2021 issue.

More from HD:

4 Inviting Boutique Healthcare Practices

It’s All About the Materials for Architect Frida Escobedo

Burnside Restaurant Sets a Moody Tone in Tokyo