Jason Holley and Paul Gulati of London-based Universal Design Studio take a bespoke approach to their projects, “resulting in better spaces and experiences for the users,” Gulati says. It’s more about sensibility than style, he adds. Here, the pair discuss how they’re thinking differently, their new digs in New York, and their signature style.

Did you always know you wanted to be a designer?

Jason Holley: From a very early age, I had wanted to be an architect. To be honest, I don’t know where the idea of being an architect came from. No one in my family or friends were engaged in design in any way. There were no interesting buildings where I lived. I just know that I loved making things.

Paul Gulati: I was obsessed with drawing from a young age. The act of making something with my own hands was a strong impulse from a very early age.

What are some of your first memories of design?

JH: When I was very young, I convinced my grandad that the built-in wardrobe in my bedroom should be torn down. I told him my parents had agreed to this (they had not). Removing it would create a much more effective space. Not questioning my word, he helped me tear down the partitions. My parents were not pleased. My grandad got in trouble, but I had a much better bedroom.

PG: I remember my father giving me old print copies from his engineering office on which I would draw on the blank side. I understood that these were old drawings of designs for something to be built (or already built) as opposed to a piece of art. In that respect, I understood design to be something very practical.

Give us a bit of your background: college, first jobs, early lessons learned.

JH: I chose to study architecture at Kingston University principally of its experimental approach to architecture and the fact that it was housed alongside other art and design departments. Having the opportunity to collaborate and learn from these other fields excited me. This passion was expanded on at Westminster University where I studied under David Greene (of Archigram). His influence reinforced the notion of architecture as a platform for exploring ideas through both built and unbuilt works.

PG: I studied architecture at university and immersed myself in a whole new way of looking and listening to the spaces and built environment around me. It was like taking a pill and transforming my perception about space and form with no turning back.

How do you make each project distinctive while also leaving your signature?

JH: A key driver is understanding the social implications, defining an experience that responds to the needs and desires of the users. Exploring how that project might lift the spirits of everyone who has the opportunity to enjoy it. This ultimately creates a unique voice for the project and one that carries our signature through our process.

Is there a challenging project that you are especially proud of?

JH: At Six Hotel in Stockholm was a particular challenge—merging a world-class art collection with a luxury hotel in a Brutalist building in a forgotten part of Stockholm. The real success of the project is in creating a social space in which engagement and storytelling are an integral and intimate part of the experience.

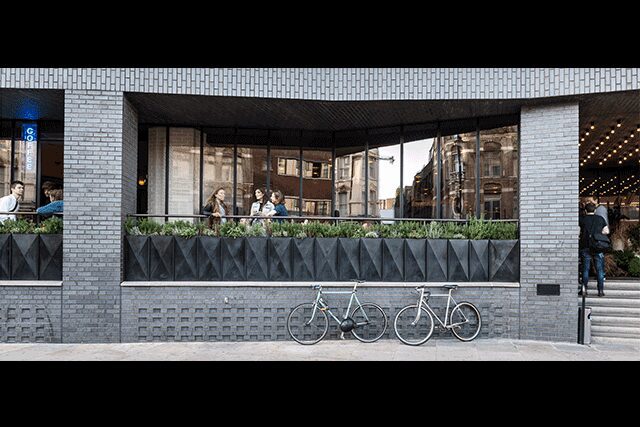

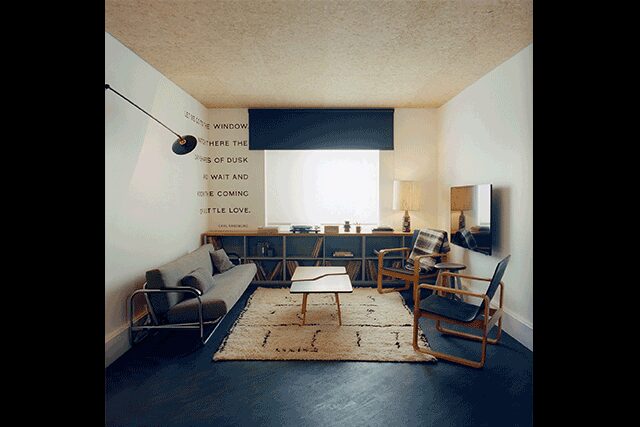

PG: Ace Hotel was particularly challenging and equally rewarding. It was our first hotel project and almost on our doorstep in Shoreditch. For these reasons there was a huge pressure to succeed and create spaces that were layered, convivial, and informal. Our intention throughout the design was to embed the hotel within the local creative community of which we were a part. The result surpassed our best expectations.

What are you looking forward to at your office?

JH: I am excited about our New York studio that we have just set up. We have been delivering projects in New York for some years and have always felt a strong affinity with the place. There is a very strong collaborative spirit in New York, which we look forward to engaging with.

Is there an architect or designer you most admire?

JH: Although not an architect or designer, the Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys spent much of his life pursuing an architectural project he called New Babylon. Explored through a series of drawings, paintings, collages, maps, models, and texts and in reaction to our depersonalized cities New Babylon outlined a model of a possible future city. It posed a question of what could be possible, a project that reinvented the world. New Babylon foregrounded the relationship between architecture, the city, and its people. It is equally cultural, psychological, technological, and political. The people are put at the center of the space—they design their own environments and in doing so design themselves.

PG: Alvar Aalto’s work continues to inspire as an architect and designer.

What would be your dream project and why?

JH: To realize New Babylon!

PG: To plan and design a new city or sector of a city as part of wider team would be a dream. Collaboration is the key and applying our learnings from a wide range of projects, especially those in the hospitality sector would be an amazing challenge on a larger scale. Our changing times require us to rethink how we approach the design of not just individual spaces and buildings, but to consider instead how we can apply human-centered design that promotes wellbeing and the democratization of knowledge on a larger city scale.

If you could have dinner with anyone, living or dead, who would it be?

JH: Novelist J.G. Ballard. I have always been fascinated with his prophetic and unsentimental visions of the world. I would imagine the conversation at dinner to veer between subjects as diverse as clinical psychology, time, altered nature, modernity, and technological fetishism.

PG: It would be my father who passed away a few years ago. I’d love the chance to fill him in on what I’ve been up to and share a few funny stories about his grandson with him.

Where would you eat and what would you be having?

JH: Odette in Singapore (designed by Universal). The artistic beauty and simplicity of chef Julien Royers’ creations would interest Ballard.

PG: We’d eat at one of Ottolenghi’s restaurants in London, and we’d share a selection of vegetarian dishes.

If you weren’t a designer, what would you be?

JH: I would run a bakery where we make just one type of bread. This bread would be widely recognized as the best bread in the world with a recipe that we had perfected over many years. People would travel long distances and queue around the block to buy the bread each morning.

PG: I’ve been making electronic music for many years and have a sound studio at home to experiment in. As an alternative career, I’d probably be creating soundtracks for films or maybe even the spaces.