Growing up in Brooklyn, my parents had good taste. [Our house] was modest, but it didn’t look like anybody else’s house. They made an effort to do something stylish. So, I grew up with this very discerning—but not ostentatious—taste. It impacted me. My father was also an impeccable dresser.

At Syracuse University, [my business partner] Steve Rubell was a few years older than me, and we became friends. He wound up doing a failing restaurant chain based on the notion of $5.95 all-you-can-eat steak, salad, and wine.

After graduating, I didn’t have any idea what I was going to do, so I thought if I go to law school, it would benefit me in some way. I learned that trying to determine what you want to do is a process of elimination. You get out there and do things, and cross things off the list.

When I graduated from law school [at St. John’s University in Queens, New York], I was in culture shock. I couldn’t get a job because I didn’t have any experience. Through a recommendation from a friend of the family, I went to work for DiFalco, Field and O’Rourke (a powerful firm) for $14,000 a year. Like architecture, being a lawyer is one of those professions where you get better later, and I wasn’t willing to pay my dues. I was always in a hurry. After a few years, I went out on my own. Steve was my first client for $1,000 a month retainer. I kept the creditors off of his back because he was undercapitalized. I rented an office and practiced for six or seven months.

Then, this opportunity with the nightclub business came up. It was the 1970s and the last golden age of nightclubs in New York; there were nightclubs for every shape and form, open all hours, all over the city. The gay movement was emerging in New York, and it was setting the cultural tone. When we went to gay clubs, it was [the wildest party]: let your hair down, let off steam, party and dance until you drop—and sex everywhere. It was this tribal energy. The straight clubs at that time were kind of pretentious and disingenuous. I didn’t feel comfortable there.

Nightclubs were still in their garage phase. Computers went through a garage phase, rock ‘n’ roll went through a garage phase, and so did nightclubs. There was no barrier to entry. All you had to do was have an idea and like to throw a party. You rolled up the rug, painted the space black, and you had a nightclub. It seemed like a good business: People were waiting in line to pay money to go into a place.

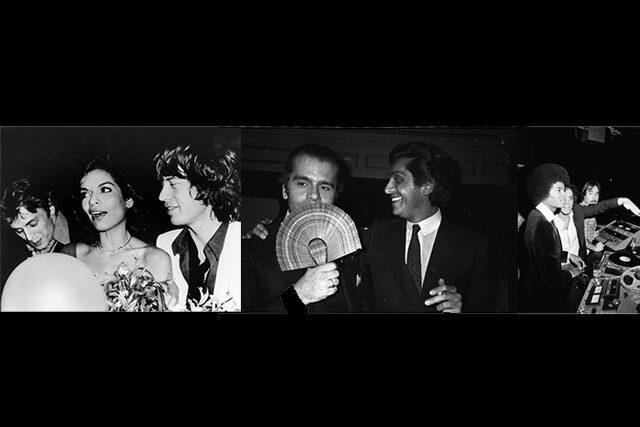

Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager standing outside Studio 54, once the CBS TV studio. “We used to do these parties that would just blow people away,” says Schrager.

We opened a club in Queens called Enchanted Garden. We were there for about eight months (just in time to catch the full impact of Son of Sam), and then we started Studio 54 in 1977 in a rough part of Midtown. When that happened, everything opened up. I was depressed for probably 10 years, dealing with my father dying when I was 19, my mother being sick and then dying when I was 23, my sister giving birth to a child with cystic fibrosis, and then being sick herself. Without my father there, it was all on me. It was a terrible time. When Studio happened, it changed my life. It was a life preserver. All of a sudden I was happy again; I was completely absorbed with it.

Nobody had ever seen anything like Studio 54 before, with the commitment to excellence, the effort to design something, the spectacular effects, the assault on the senses. The diversity created another layer of energy: rich and poor, old and young, gay and straight, black and white, it didn’t matter. Celebrities started coming and nobody cared. And nobody bothered the beautiful women. That was ensured by the door policy.

The velvet rope was business motivated. When you want to have a good dinner party, you put somebody who’s talkative next to somebody who isn’t. That’s what we were doing, but in the public domain. The actual experience—this ability to be completely free with no fear of reprisal—combined with the era (after birth control, pre-AIDS) was the magic sauce.

(Left to right) Dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov with Bianca and Rolling Stones frontman Mick Jagger at Bianca’s birthday bash in May 1977; fashion designers Karl Lagerfeld and Valentino Garavani; singer Michael Jackson, Rubell, and Richie Kaczor, one of the club’s most successful DJs, in the DJ booth.

We did Studio in six weeks to make sure we opened before everyone left for the summer—that spontaneous energy, acting on instinct, everybody working, was a lot of fun. We hired up-and-coming designer Ron Doud, we had a lighting guy, and a landscaping guy for the flowers. We were trying to do something that was conducive for socializing, hanging out, and bumping into people. We separated the dance floor—it was the heart of it. The bass was so incredible you actually felt it.

We had moments throughout the night. They would only be a minute. Something would come in unexpected and lift the crowd up a notch and go away just as quickly as it appeared. We never wanted to have a [full] performance because we were afraid to stop the party. We were afraid we might not be able to start it up again.

Studio 54’s original lobby hallway, which led to the main room with the dance floor, where found moldings were painted a high-gloss burgundy to match the matte wall color, and four dramatically lit 16-foot-tall fig trees complemented the leaf-patterned carpet.

Steve and I completed each other. We both had natural areas of interest, but they weren’t mutually exclusive—it was one plus one equals three. The first day we opened the club in Queens, he went to hang out with all the kids in the bar, and I went to the DJ booth to play with the lights. It was said that Steve stayed too late and I left too early. So Steve got all of the publicity and credit, and that was fine with me because I got it too. If he got it, I got it. It was that kind of friendship. There was a generosity of spirit between us.

On Studio 54’s first night, we were working right up to when the doors opened. Then, I got a call from Steve at about 5 a.m. that we were on the cover of the New York Post. Cher was on the cover. That was unheard of—it was the feeling of utter joy. From then on it was nonstop.

I could do another Studio 54 today because it’s a human condition. People like to socialize. There are things that changed: The cell phone is an element of that, fashion has changed, but people still strive for that feeling of absolute freedom. That doesn’t change.

I didn’t want to do the Palladium nightclub [after serving a year in prison from 1980 to 1981 for income tax evasion at Studio] because I didn’t have a new idea for it. It was only more: We spent more, we did more. Steve intrinsically enjoyed being in the nightclub business, but I didn’t. I liked the creativity, I liked the gratification, but I didn’t particularly enjoy it. I had my idea with Studio, and that was it. But we did it because we were doing a hotel at the same time and we wanted to have a source of cash in case it went over budget.

The lobby of the Paramount Hotel in New York’s Times Square, Schrager’s first entry into what he calls “cheap chic.”

The hotel business was a natural adjunct to the nightclub business, even though it doesn’t look like that on the surface. But the goal is the same: taking care of people. I read a lot of books when I was away, and we wanted to do a hotel that we liked, that manifested our popular culture. We wanted to do something that was stylish and felt residential, sophisticated, and cool. We were willing to break every rule in the book. It was also around the time when Donald Trump and Harry Helmsley were opening up hotels and they were playing up the old generation and the new generation, and it sucked me right in to do better.

Our first hotel, Morgans in 1984, used to be an old rooming house with hot plates in every one of the 200-square-foot rooms. It was a rundown, dumpy place. We got the building because the guy that we’d sold Studio to couldn’t pay the promissory note. We [traded that for his] interest in a hotel that his father owned.

We never considered [not getting back into business after jail]. It was always, ‘What’s the plan now? What are we going to do to get back?’ Life would have been over. My father used to tell me there’s no harm in falling down. The issue is not getting up again.

Philippe Starck created a dramatic entrance hallway at the Delano in South Beach with white curtains and columns.

At Morgans, we took all the loose furniture out of the room to make it feel bigger. We lowered the furniture to 16 inches so it felt calmer. We put a thermostat [in the rooms] to make people feel that it was central air conditioning. We had black and white matte tiles, stainless steel sinks, and white towels. We used glass shower doors because we didn’t have a bathroom big enough to fit a regulation-sized tub.

Sometimes when you don’t know anything, it’s an advantage. Then you’re willing to try anything that makes sense. You’re not burdened by the rules; you think outside of the box.

Morgans was a natural success and what everybody was waiting for—a hotel that didn’t look like a hotel and was unlike any other out there. It felt different. It was cool, more sophisticated, and more refined. We had worked with [the late] French designer Andrée Putman, which guaranteed our approach would be different by definition. We learned every rule, and those that made sense, we followed. If it didn’t make sense—patterned sheets and carpets, indestructible bedspreads, vinyl on walls—we didn’t follow it.

I remember a financial backer and I talking about a table in the guestroom, whether it should be 25, 26, or 27 inches tall, and he said to me, ‘You’re never going to be able to get this thing done if you’re going to be involved in every single detail.’ I don’t know how else to do it. When you amass all of the details, like when you put diverse people together, a [natural] alchemy happens. Every detail is important because I don’t know which detail is the detail that pushes something over the top.

The name Morgans was because it was in the neighborhood of the J.P. Morgan library, which was a very significant architectural building by Stanford White, and the Morgan was also my favorite car when I was growing up. We just added the ‘s.’ Since that was the first name we used, we adopted it as the name of the company as well.

The Royalton in 1988 [the first of many collaborations with Philippe Starck] had a big lobby with a very low ceiling, and it was the place to go. The restaurant [helmed by chef Geoffrey Zakarian] and bar were crowded with people who weren’t staying in the hotel, which was a new idea. We wanted people hanging out in the lobby. The secret was that the restaurant had to appeal to people who live in the city because hotel guests want to go where people in the know go. That was the fundamental change the industry realized: You didn’t have to have [F&B] as loss leaders.

Philippe is an iconoclast. He’s one of the most creative people I’ve ever worked with, in a very undisciplined way. He’s a great product designer. The thing that made me want to work with him is when I saw the project Café Costes with a bathroom no one seemed to know how to use. He reinvented the French brasserie, which is hundreds of years old, and I thought if he could reinvent that and a bathroom, he can certainly reinvent a hotel.

When my father died, it changed me. It felt like the rug got pulled out from under me. But in a funny way, Steve’s death [from AIDS in 1989] had a bigger, more profound impact on me because he was deeply involved in my everyday life. My life had to change from one day to the next. There were a lot of people that were doubters—I didn’t know how to deal with the media, and I had to do Steve’s job as well as mine. But I found I wasn’t shy when I was talking about the work.

We were best friends. We shared houses together. He was my first phone call in the morning, and my last phone call at night. I never had another friend like Steve.

We couldn’t get a liquor license [at first because of our conviction], so we opened Morgans and eventually Royalton without one. It’s like having a nightclub without music. But if you do something outside of the box, it strikes people in a different way. That’s when you have a chance to excite people. They liked the hotels. Plain and simple.

I can’t tell you how much it meant to get the liquor license six years later—it was the vehicle to a successful business. And it was the beginning of getting back all that we lost. Steve and I applied, and got it in due course, but unfortunately, Steve had already passed. It, of course, culminated when I got the pardon from President Obama

[in 2017], because then I got back everything that was taken.

A dramatic light bulb installation covers the ceiling of Gramery Terrace at the Gramercy Park Hotel in Manhattan, a collaboration between Schrager and artist Julian Schnabel in 2006.

Going to Miami [with the Delano and then the Shore Club] was very important because it was the first location outside New York, and the first indicator that we weren’t just a New York phenomenon. We were a catalyst for development in Miami and then the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles with the Mondrian. I like being a pioneer. I love doing stuff that blows people away.

Morgans had become a big company. I had sold a substantial interest and my partners, who were primarily financial guys, wanted to go public. I didn’t have any interest in that—I was interested in doing special projects. I had done what I could do with Morgans. I was ready to do something else, to start over. I walked away in 2005 from what would have been a handsome financial reward, but I didn’t care. I was ready to go.

It’s a simple explanation [for why Morgans hotels are still around]: It’s always about the product. It’s not about the reservation system, or about all the other things that generic properties concern themselves with because they have nothing distinctive to offer. It’s about the product. If it’s done well, it will last forever. The most amazing part is that the hotels haven’t changed much in the last 20 to 30 years. I guess I get the last laugh.

The Herzog & de Meuron-designed luxury residential project, 40 Bond Street, in New York’s NoHo neighborhood.

I was never interested in having the biggest hotel company, and I probably didn’t have the skillset to do it. That’s why I did the Marriott deal with EDITION. I wanted to do something on a bigger scale. I’ve learned to deal with the Marriott way of doing things the way they’ve learned to deal with me. People would say, ‘Ian’s selling out.’ Bullshit. I couldn’t sell out; it’s going to be a good product and they’re all going to be different. If the product wasn’t good, I wouldn’t do it.

The idea was to [marry luxury and lifestyle]. To do something just as stylish, just as glamorous, with exciting food and beverage and great service, so you’re not giving up anything to stay in the coolest place in town. It just makes sense.

The Sanya EDITION comprises teak-clad private dining pavilions on the resort’s mandmade ocean, courtesy of Schrager’s in-house team, CAP Atelier, and SCDA.

PUBLIC is intended to go into the space dominated by the Courtyard by Marriott and the Hilton Garden Inn. The level of finishes are a bit higher, but it’s meant to have lower rates. Cheap chic. It’s the same void I saw when I did the Paramount [in 1990]—it was the prologue to PUBLIC. I saw the opportunity for somebody to come in and do something with pizzazz. I love that end of the market. The luxury end in the hotel business is not the moneymaking end. If you can bring style, quality, and a creativity to that end of the business, that’s where the market’s huge. We always had small rooms [like PUBLIC does, and many hotels today]. Once you started banging on the walls of these old buildings, you didn’t have a budget.

Public New York is Schrager’s “luxury for all” concept that speaks to its surroundings in the Lower East Side with a garden entrance.

I wanted to do the [recent] Studio 54 book and film for a couple of reasons. First of all, I was and still am embarrassed by what happened, to be so stupid. I didn’t think we were getting intoxicated [with the success of Studio] because I still had my same friends, and I wasn’t spending a lot of money. We were working all the time, so we didn’t realize that we had lost our way.

We truly loved Studio. We were trying to protect it; we didn’t want to give it up. That was it. Forty years had gone by and there were a lot of revisionists out there, a lot of people who were saying things that were complete nonsense. I didn’t like some of the movie’s personal parts; I am a private person. But I wanted to tell my [five] kids what Studio was to me—an accomplishment on a creative level. I wanted to set the record straight. I often quote Berry Gordy, who wrote in a book, ‘If the lion doesn’t tell his own story, the hunter will.’

I still look at every single thing. The intensity and the focus haven’t changed one bit. What’s changed after all these years and what I’ve learned from Marriott is that I can do a lot more than I did before. I have a lot more confidence that I know the universe of possibilities—it’s not open-ended. It doesn’t take me very long to make a decision. I don’t agonize the way I used to over everything. I was afraid of making mistakes, and I’m not afraid anymore. I have great people working with me who have been here a long time. They do a lot of the work and deserve a lot of the credit. I am enjoying [the process] a lot more because there’s no slippage in the quality of the work. It’s easier for me than it was before. And I still love it. That’s the secret weapon.

I haven’t done everything I want to do in the hotel business. I’m still very ambitious. I’m thinking about doing a dramatic movie, and I’m coming out with a vodka. I would like to get nominated for an Academy Award [for the Studio 54 documentary]. I wonder if I am still not satisfied because I lost so many years with the Studio debacle and when my family was sick. But I don’t have many regrets. Well, maybe I regret that I didn’t buy the house next to me at the beach.