I grew up in Hampshire, very near Southampton, in England. It’s in the countryside, so I’m a country girl. I have two older brothers, and I was a tomboy. My parents were of the school that if you could remember the last time a room was decorated, it didn’t need doing. Nevertheless, I remember clocks ticking and trying to slide on slippery wooden floors, so I was always interested in interiors.

One of my first jobs was working for an auctioneer, going into people’s homes that were being decluttered of furniture. Things were being taken out, so I got to look at different interiors all the time. Then I worked for Polish architect Leszek Nowicki, who had a very different idea of design than a lot of other people at that time. My role was menial—making tea and going around with a tape measure.

Tim [Kemp] was one of his clients, and was running a student accommodation. Tim was practical. Lots of people had pie in the sky ideas of what they wanted to create, and often it was abstract, whereas Tim was hands-on. He would stand up the ladder and paint the ceiling himself.

When Leszek got married, he sat Tim and I next to one another, so that’s when it started, but it was an on-and-off relationship because I never knew whether Tim liked me or not. I remember going to a house he was building, and in the basement he said, ‘We’re going to need a cat door in here.’ The builder that we were using said, ‘But you don’t have a cat.’ And I thought, ‘But I do. Maybe he is more interested than I think.’

He never asked me to start working for him, but I realized that with Tim, he was such a workaholic, the only way that I’d get to see him was to become involved. Very often as a woman, you just have to get in there and start. We would have terrible arguments because if you believe strongly in something, you’re going to fight [for it]. Now we’re like a couple of sumo wrestlers: We know when to circle and go in for the kill. It’s gotten easier.

Tim’s accommodation was linked with Richmond College in Virginia. It was four or five beds in one room. There was nothing glamorous about it, but it was fun. On Friday evenings, there would be someone playing guitar and all the students were there. We were little more than students ourselves, and we enjoyed that.

Tim had this idea to take an old, 2-Star hotel and create a boutique hotel. This was in the ’80s when Craig [Markham, director of marketing and public relations at Firmdale Hotels] started working for us. He was a backpacker from Australia, but he never went back. A few of the people working in our company all joined us when we were young, and they’ve grown with us. We always say that we’re all pretty unemployable, so we had to stick together.

It was difficult to get financing because people didn’t understand small hotels, and they certainly didn’t understand boutique concepts. But we could see there was a market there, and we didn’t like what existed—the feeling of large hotels that had little character. We felt there should be much more of a sense of arrival because hotels were a part of the adventure of travel.

Our first London hotel was Dorset Square—which we sold and bought back again—a regency building on the site of the first Lord’s Cricket Ground, so that was a great thing to make a bit of a theme for the hotel. We were learning as we went, and there’s something about the arrogance and ignorance of youth that pulls you along. In the basement of the hotel, we were building a restaurant, and somebody said they knew Anton Mosimann, a distinguished restaurateur in London. So we said, ‘Maybe he can come and have a look at the building site.’ I remember meeting him. He was Swiss and wearing white patent leather shoes, and the rain was dripping from six floors down into the basement. He took one look at the space and said, ‘You will never cook a meal in this restaurant.’ Like, go home, forget it. We thought, we’re going to continue and we’re going to do it. A year or so later, he did come back and say, ‘Well done. I was wrong.’ We were already, by that stage, winning a following of people who felt like us.

The next one we did was the Pelham, in what was then a rundown hotel. It’s slightly more difficult during the second and third hotels because then people are expecting more and more. But it never felt like work, and we had fabulous buildings. Covent Garden Hotel was an old French hospital. Charlotte Street Hotel was a dental warehouse.

I never liked the idea of brands, so every hotel has to speak for itself; it has to be individual. That’s what makes it so fascinating for people to come and stay because although there’s handwriting, every building has its own signature. Charlotte Street Hotel is all about Bloomsbury, because that’s where it is in London. There’s such a fabulous archive and interesting things to learn about the Bloomsbury Group—including Virginia Woolf, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell, and the Omega Workshops. That was a wonderful resource to look into, and at that time, we could buy Bloomsbury art. It was out of favor, so we could afford to get quite a good collection.

During our renovations, we have found amazing things that have been lost and forgotten. With old buildings, of course, the rooms are never going to be straightforward. You’re going to have nooks and crannies and fireplaces, and differences of heights in the floors. After all the renovations, walking through the door is always the best feeling. In a sense, you feel as if you’ve handed it over. It’s got nothing to do with you, and then the guests create the character and add to the curiosity.

When you look at London, it’s a series of villages altogether. So, in a sense, your building is part of that village. When we came to New York, which was frightening because it was a graveyard for so many British companies, it was the same: Every village and every area has its own character. We had this original idea, art inspired by the written word because I love the salon concept of the artists, meeting. And Crosby Street and SoHo are areas for creative people and artists. We have Anselm Kiefer and Callum Innes in there, a big Botero cat outside. Then, as we were walking around the streets, I couldn’t get over all the dogs I was looking at. In the end, we had this incredible dog theme, which allowed us to find great artists to commission and also has inspired so many guests to send me pictures of dogs, opening a dialogue with them.

When we were building the Crosby Street Hotel, we wanted it to be a green building, and we got the first LEED Gold rating in New York for it. We had all the bicycle racks outside, a green roof with chickens, and were buying locally. We’ve worked a long time to build this more sustainable image. It works for us. It’s what our clients want and we’ve got into the swing of it now, so we’re not turning back. Jessica Black, who’s worked for us for quite a few years, is the main one who’s been looking at sustainable ways of even washing our sheets. We have our own laundry, and it has tumble washers, which use less water. We have bees on our roof at the Ham Yard, and we’re going to have our own bakery. We worked out that we use over 3,000 bread rolls a day. If we’re making our own, so much the better.

The Whitby in Midtown is very different in terms of scale and location. Being in New York is a bit of a battlefield. It’s a huge anthill of commercialism, and I wanted to make the Whitby into a little fantasy hideaway that you wouldn’t expect to find. It wouldn’t be English, it wouldn’t be American, it would be filled with interesting artworks and would have a good feeling and character to it.

The Warren Street Hotel, in the works in Tribeca, is a new-build. It’s a dream project. When you’re building a hotel you’re so lucky because you have drawing rooms, event spaces, restaurants, bars, bedrooms, roof spaces. What more would you want?

I love to have interiors that aren’t straightforward, capture your imagination, and make the most jaded businessmen look around and say, ‘Oh, that’s different.’ I’ve always loved the color. I’m much more frightened of beige, white, or gray. Although I appreciate these interiors that are basically one color, I can’t do it. Color makes you happy, and it’s one of the easiest ways to do it. Adding color adds life.

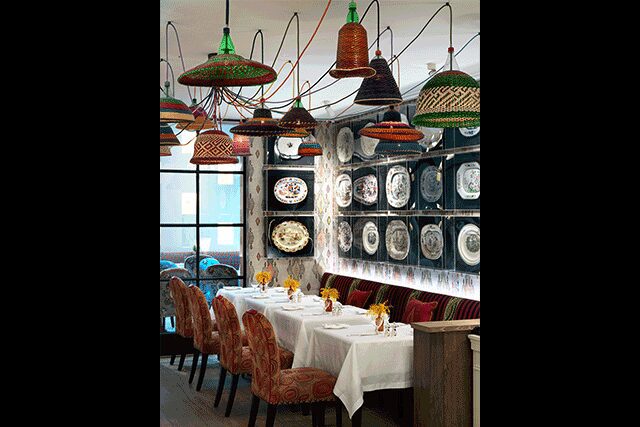

You can put a great collection of almost anything together, it doesn’t matter. At Ham Yard, we stuffed newspaper inside bowling shoes that we bought on eBay. By putting them as a collection on a massive wall surrounded by bowling balls, they look fascinating. At the Whitby, we took fabulous old dinner plates that are works of art and framed them in such a way for you to recognize that. When you get a lot of them together, they start speaking to you. I was a bit worried to hang 57 baskets above the bar at the Whitby, but it worked out in the end. You have to take a few risks. The basket is such a humble little thing, but they have so many different uses. And whether it was baskets on the back of ponies bringing fish from a Scottish porch, or collecting apples in Kent in a great big horn of plenty, suddenly, when you start looking at all these baskets and seeing how useful they all were, it becomes quite interesting.

We love craft. You can have a lot of technology and go in that direction, or you can have that artisanal feel. That’s where we have gone. When I’m looking to find artists, it’s people who love to use beautiful pieces of wood, simple, organic things. We like the ones who are independents, who are going it alone. It’s a great start and you can build a rapport. They’re helping you. You’re helping them. Of course, they then get so famous that you can’t afford to use them anymore. We’re democratic in the way that we hang art. We have well-known artists beside artists who are just coming out of art school.

One of the hallmarks of our design is oversized headboards. With a high headboard, you can see the fabric and the pattern. We say every headboard tells a story, and so you can create a story. It’s the one focal point within the room where you can have a lot of fun. Then, if we find great artists, we can ask them to make their own headboard, like Kumi. She’s half Japanese and her mother sends over kimonos from Japan. She also collages, sews, and adds color to these beautiful pieces of work. She was only making bags before, and we said to her, ‘Have you ever thought about doing this?’ We’ll send her the pattern for the headboard, and then she works her magic. We’re lucky to have found her.

There’s that sort of WeWork type of atmosphere that I love—the idea of refectory tables and people working away, the teamwork of it all. But I don’t want to come into a hotel and feel that I’m coming into an office. I don’t mind having an area set aside, but that’s not the main feel of my hotels. There’s a lot of art and design that is technical, austere, and masculine. I like that, but I like it in my kitchen or my bathroom. In my bedroom and in my drawing-room, I want a much more embellished, slightly more feminine look.

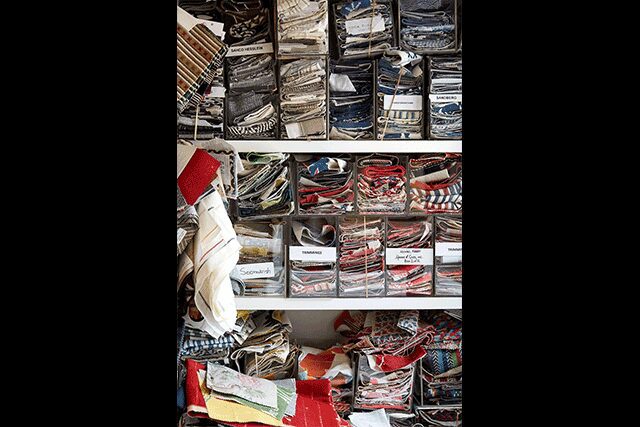

Product design was an organic process. If you asked me 20 years ago if I would be doing this, I would be surprised, but I’m so delighted working on our different fabrics—linens, cotton, twills, chintzes—and the ceramics and furniture design. I have learned so much, and I’m continuing to learn by going to places like Belgium and talking to third- and fourth-generation weavers there.

We also started a blog that’s a day-to-day look into our design office. We’re putting embroidered fabric on chairs or collaging fabrics onto sofas, and we found that people were interested to know more about creating things like that. We have a blog meeting every week, and it’s like a show-and-tell of what’s happening in the office and the best exhibitions that we’ve seen.

Interior design is often about being outside. It’s standing up a ladder. It’s going into rooms that are not completed. It’s going onto building sites. When a place looks fabulous, I’m not needed, so interiors are very much about being in uncomfortable places.

You never listen to people’s advice halfway through a project. You have to have your ideas and believe in them, and then you have to see them through to the end because people will say, ‘I don’t like that idea.’ And you have to say, ‘Wait until it’s completed, and then you can tell me what you think about it, but in the meantime, have a bit of faith.’

We’ve always had our training school, but never in one place. We have 30,000 square feet of warehouse space near Heathrow Airport, so we decided to make part of that our Firmdale Training Academy, our latest project. With our own school, it’s important that everybody feels what they’re doing is valued. It doesn’t matter if you’re starting off as a chambermaid or someone filling the minibar, you have to feel that one day you’re going to be the general manager. You can watch staff leave the building, and if they’ve had a good day, there’s a smile on their face. They’re ready for the rest of the day. If they’re hating it, they’re coming out and they’re looking dreary. And that comes over to your guests, as well.

I’m working on my fourth book. You always start thinking, ‘I’m never going to fill every page. What am I going to do?’ And then, at the end of it, you’re taking things out there’s so much. I don’t think about time off. I love design, so if I’m going to the theater, I’m looking at the set design. If I’m going to the ballet, I’m looking at their sets as well. It’s not just work, it’s a way of life. hd

Hear more on HD’s “What I’ve Learned” podcast at hospitalitydesign.com