After finishing graduate school in 1995, the Japan-born interior designer Ryoko Okada took a job at powerhouse New York design and architecture firm Perkins Eastman. It was there she met Israeli-born architect Eran Chen, one of the youngest principals at the company at the time. Their partnership flourished, and when Chen left to start ODA in 2007, he asked Okada to join him. “I immediately said yes,” she says.

The design and architecture firm’s philosophy reflects the yin and yang of Okada and Chen’s personalities. Their work is at once thoughtful and ebullient, cultivating projects that go beyond the superficial. Architecture, to them, is a world-building endeavor that should ultimately benefit the greater good. The reserved Okada is meticulous in her pursuit to carve out distinctive interiors. In contrast, the outgoing Chen considers the big picture.

A rendering of a courtyard at 561 Pacific condominium in Brooklyn, New York

“My abilities are in creating the overall concept, the coherence of the storyline, the general atmosphere that anchors the idea around a narrative,” Chen says. He tells a story that becomes visual, while Okada’s “brilliance is in bringing the tactile and the small scale into the details,” he adds. “She picks up the story where I leave it and continues it with a fine touch.”

There were a few lean years in the beginning, especially while starting a firm at the peak of the recession, but they survived thanks to a few luxury apartment renovations and Bread Box, a small bakery in Long Island City, New York that became integral to ODA’s identity. They covered the existing exterior with 2,000 rolling pins and worked with a local nonprofit to tie it into the neighborhood by inviting the community to donate money to have their names inscribed on the pins.

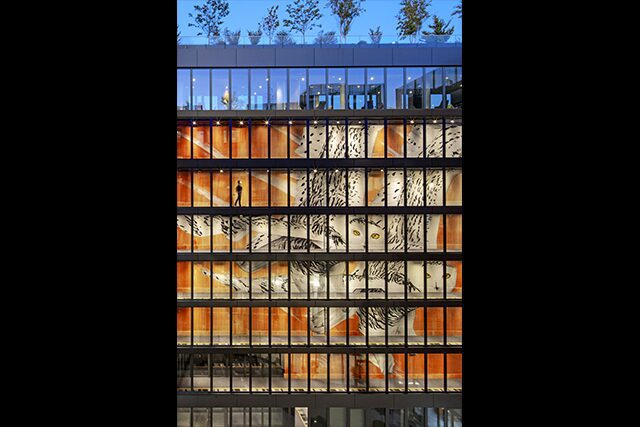

This community-first mentality became a firm signature, and they’ve successfully transformed neighborhoods into living, breathing, bustling organisms ever since. Consider the residential new-build Denizen Bushwick in Brooklyn, New York. The community board was hesitant to have a high-rise pollute the streets of the artist enclave, so Chen and Okada reframed their approach. Chen, for his part, started nonprofit ODA Public Engagement in Neighborhoods (OPEN), which partnered with local organizations and artists to design 15 large-scale murals that adorn everything from corridor walls to a parking ramp near a public garden. The process fostered community engagement, ensuring the building is as woven into Bushwick’s fabric as the people who live there. “It was the [artistic] community that inspired us,” says Okada.

Denizen Bushwick

Yet, many of the projects Okada and Chen handle are adaptive reuse, which allows them to champion historic buildings and celebrate their past via a modern lens. “When we start a project, we look at what’s around: the history, the people, and what we can bring there,” Okada says. “It’s not so much about the materials or fine details but what the building feels like. We want to make a community within that scope, but we also have to be open to the existing community.”

The Book Tower in Detroit, for example, is a soaring Italian Renaissance building that fell into disrepair and required precision and appreciation to bring back to life. With ODA’s delicate touch, it will become a thriving mixed-use space in the heart of the city when its completed in 2022. An artisan, in fact, is painstakingly restoring the historic glass skylight to its original grandeur. “When we come in to write a chapter in a book that is already written, we’re adding a layer to something,” Chen says.

The atrium lobby at the Book Tower in Detroit, shown in a rendering

Among those significant stories is Rotterdam, a city that was nearly destroyed during World War II. Of the handful of surviving buildings of the Rotterdam Blitz was the city’s beloved post office, a beautiful structure that sat empty for 12 years. Set to open in 2023, ODA’s restoration will convert the site into a mixed-use marvel that will comprise a new tower, a 226-room Kimpton hotel, and a series of retail and F&B spaces—all centered around the Great Hall, which doubles as a civic space for the city. “One could easily see how this project would become a fortress for rich people,” says Chen, “but we’re bringing this historical building back to the people of Rotterdam.”

Cities are evolving and how people live is changing. In response, ODA is leading the charge for more inclusive spaces. The old way of thinking about architecture is no longer sustainable, they say. “We are dealing with spaces where people live,” says Okada. Adds Chen: “Architecture can transform not only individuals or families, but also communities in a way that you can’t predict. The idea is to envision how a structure or place could [change] the quality of someone’s life for the better. To us, that’s the best part.”

420 Kent in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

An interior courtyard anchors a hotel concept in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, shown in a rendering

Denizen Bushwick features 15 large-scale murals, including Snowy Owls by Aaron Li-Hill

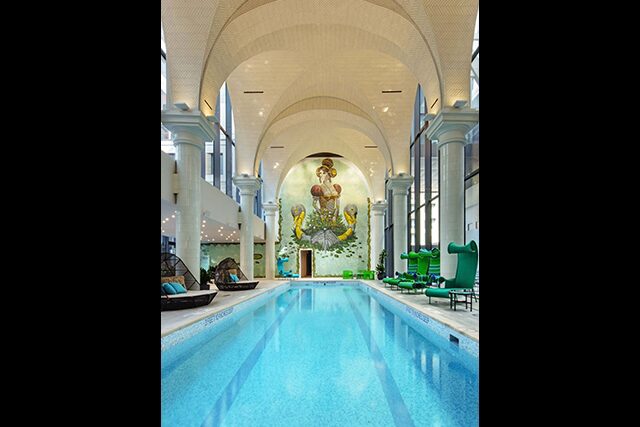

A mural by Pixel Pancho punctuates the pool at Denizen Bushwick

The 561 Pacific luxury condominiums in Brooklyn, New York

Exterior detail, shown in a rendering, of the new tower at POST Rotterdam

An open courtyard at the Rodezand wing will define the POST Rotterdam, shown in a rendering

A rendering of a residents lounge in the Brooklyn Grove

The lounge at Brooklyn Grove

Photos by Eric Laignel and renderings courtesy of Forbes Massie and ODA