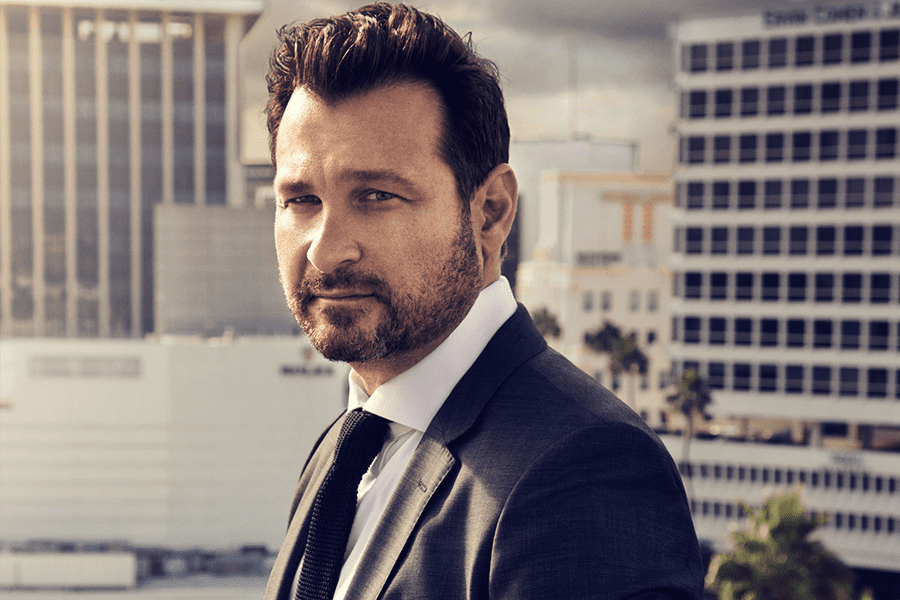

Jason Pomeranc

Details

Cherishing the creative process, hotelier Jason Pomeranc continues to push it to its limits and redefine the hotel experience. First, in the early 2000s, as a cofounder of the industry-disrupting Thompson Hotels brand before following up his success with SIXTY Collective, the operating company of SIXTY Hotels. Pomeranc is also behind the recently opened, theater-centric Civilian hotel in New York—a natural fit for his design approach which he describes as cinematic. When entering a building for a new project, he likes to envision people in the space and watches it play out like a movie, which he then uses as inspiration.

Subscribe:

Stacy Shoemaker Rauen: Hi, I’m here with Jason. Jason, thanks so much for joining me today. How are you?

Jason Pomeranc: I’m great. Thanks for having me.

SSR: Of course. It’s so good to see you. Okay. We always start at the beginning at this podcast. Where did you grow up?

JP: As a child, I grew up in Queens, New York, and then in my teen years, my family moved to the Upper East Side. I’ve been, for the most part, a New Yorker ever since with little…into West Coast and London and some other places, but I’m a bit of a New Yorker through and through.

SSR: Was there an early inkling that you had a love of design or any early memories of hospitality that might lead towards the career that you have?

JP: I was the youngest of three children by a significant amount. By the time I was coming into my preteen years, my parents had had enough of the traditional, “I’m going to take you to camp,” and, “I’m going to take you here.” I just traveled with them. It was at the time seemingly odd for a 10, 11, 12-year-old to travel with groups of adults in all these places, but in retrospect, it really helped form this perception at such a young age of going to hotels and these interesting restaurants and experiences that just you normally wouldn’t be exposed to until you were much older. It redefined what was normal for me in the perception of hospitality and engagement, and something odd happened.

I finished high school, and I was applying to colleges. This is a little bit of inside baseball, but I was applying to various schools, and at a very competitive high school. Most of the kids went to Ivy League schools, so everybody was looking for an edge. I decided I was going to apply to Cornell Hotel School, not because at the time I knew that I had a passion for hotels, because I thought that somehow I had the type of personality that could engage. I went up for an interview with the dean. Somehow I managed an interview with the dean. He just asked me a question I was completely unprepared for. He goes, “Well, why do you want a career in hotels?”

I guess at the time, I hadn’t at least consciously thought about it, but I just organically said, “Well, hotels have stayed the same since fundamentally in the ’50s when Hilton and Marriott kind of evolved and became these international players, and they brought America to the world, but it was all about standardization. It wasn’t about individuals and creating unique experiences. I think now, particularly with aesthetic, we need to just change and be liberated from this tyranny of beige and..” I went on this rant that I didn’t really know that ended up being my entire career, which was really strange because it just synthesized from that one moment of pressure. He was kind of shocked. He was like, “Whoa, okay.”

In the end, for various reasons, I ended up going to NYU. I did get into Cornell and went up there many times time since then to participate in programs, but I think from that moment, I realized, “That’s what I want to do.” It became synthesized, and all those childhood experiences came to the forefront. I spent a lot of time just evolving that aesthetic pallet and studying. I was fortunate enough very early in my career to meet eccentric, slightly odd, creative characters that to a degree mentored me and spent hours and hours and hours exposing me to things that a traditional professional relationship just doesn’t have. Normally, and anybody who’s in the industry knows, a client goes in, and you retain an architect or a designer or a creative director. You have a certain amount of hours together, and you have a very specific job description.

I wasn’t like that. A lot of people early in my career were just savant tutors and couldn’t even draw a straight line. I think that gave me the opportunity to develop my own perspective of how design was evolving in hotels and creating my own look and not really be locked into what the trends were at the time.

SSR: Right. Who were some of these early influencers in your life? What were some of your first roles?

JP: Yeah. Definitely the two guys that were the most powerfully influential were Jim Walrod, who passed away a couple years ago, who they used to call the Furniture Pimp because he wasn’t a traditionally trained designer. He got his initial creative experience… Another story that I always thought was bullshit and then actually validated to be true was that Jim, when he was a teenager, was applying for a job as a window dresser at Bloomingdale just because he saw it in the paper and he needed a job. On the way there, he stopped at Fiorucci to look around, to get creative ideas, and he met Andy Warhol randomly. He asked him, “Hey kid, what are you doing?” He goes, “Well, I’m applying for this job,” and gave him the whole story. He goes, “Go tell them that you’re going to put mannequins that all look like Andy Warhol and the real Andy Warhol’s going to go stand there.”

Apparently, this happened, and Jim ended up working for Andy and became his gopher. Andy taught him about furniture and art and artifacts. That’s how he developed this network of underground furniture dealers and back of warehouses where they had all these antiques that you couldn’t get. Jim was very, very influential in educating me on various periods of design and how they reflected what was contemporary and modern and how each period kind of intersected with the other. The other gentleman was a guy named Steven Klein, who just died recently, who was a branding consultant who could not work a computer for the most part and had a library of old books and magazines that he actually got donated to a museum.

He was also a savant that had an incredible visual library in his own mind of typefaces from the 1950s and fashion references and just cultural relevancy. We’d sit for hours and talk about these things. That helped form the foundation that… When I went in then to talk to what now are the globally-recognized, world-famous designers, I was armed with a certain amount of knowledge that other clients didn’t have because I had this secret education that was going on in the background. I think ultimately that made me a better client. I think over the arc of my career, it made better projects.

SSR: Yeah. How did you meet Jim and Steven? Did you work with them or just knew them?

JP: Yeah. A mutual friend introduced Steven to me to do a little bit of branding work for us when we first started with 60 Thompson, and he helped redefine the original Thompson logo. That was how we started working together. Jim was an introduction… Interestingly, I don’t actually even remember who was the initial person who introduced us, but we did end up collaborating on several projects, including a hotel that I did early in my career called Gild Hall and ultimately SIXTY LES and my homes. He did my New York loft, which has been published a bunch of times. He did my LA home in conjunction with a gentleman in Brad Dunning, who’s a very well-known mid-century expert. We had some fun, interesting experiences. I think over the years, even when I was working with globally-recognized designers or creative agencies or big groups, I often still went back to them to just bounce ideas around and see if my perspective was still there.

The Civilian; photo by Johnny Miller

SSR: Did your mom and dad have a love for design? Were you surrounded by design early on, or was that just something found on your own?

JP: They had an appreciation for nice things, but in a genre that is completely unrelatable to what I do. Everything’s very Baroque and gilded and fancy, and that’s the type of hotels and the type of restaurant you go to. While it certainly didn’t influence my actual aesthetic, I think just the appreciation of objects and craftsmanship and the idea that a chair or a figurine or something has this history to it, that I think became important, as opposed to just, “This is disposable furniture. When we get sick of it, we throw it out.”

SSR: Yeah. Were they in the creative fields? Did they work in anything design or hospitality-related?

JP: Well, my father spent most of his career as a real-estate developer, but mostly very traditional housing and multifamily. My mother’s job was mostly to keep me out of trouble, and my brothers. Thankfully, they are still a good stopgap of whenever you think you know too much, they remind you that you’re still 12 years old in some extent.

SSR: Yes, that is their specialty, isn’t it? Okay. You went to NYU. What were some of your first jobs out of college?

JP: Well, in college, for a period of time, and it’s funny how small the world is… I started to dabble in nightlife and entertainment, and I actually used to throw parties at a place called Sticky Mike’s Frog Bar, which ironically was owned by Josh Pickard from NoHo Hospitality that owns The Dutch and Locanda Verde, and Aby Rosen from RFR and his partner, Michael Fuchs. They were all super young. This was a little club they had under a place called Time Cafe, which is now where Lafayette is. That’s how I started to get into that world a little bit. But I moved around. I worked at Bear Sterns. I ended up going to law school, so I ended up practicing as an attorney for a while as well.

JP: I wanted to get as much exposure. The field of hotel development and operations is deeply complex. You need to have weapons beyond just the knowledge of the pure hospitality aspect of it. I wanted to gather in as many skills as I could at that age. In many ways, it was very conflicting because, yes, I liked being out there in the mix and creature of the night and going and traveling the world and seeing new places, but I also wanted the structure of all the skills that I would need to compete in this world.

SSR: Awesome. Okay. You were saying that you got all these different experiences. You did bear Stearns, went to law school, and then practiced law. What made you ultimately decide to start Thompson Hotels? What was the idea, and how did you make that actually happen? Because a lot of people have good ideas, but making it happen is half the battle.

JP: I’m sure. Well, in the year, probably, two of my legal practice it was pretty apparent that I really did not enjoy that part of the… Law school was nice in theory and intellectually stimulating, but it wasn’t in practice what I wanted to do every day. I left in order to develop, basically. I’m not sure we had a specific… because at the time, my older brothers and I talked about it a lot, and the family holdings had started to delve a little bit into hospitality, but more traditional Hiltons and airport hotels and some stuff in Manhattan that was budget-independent, but not to what we were going to do. We decided that the real gap was there was something missing in the European model of small luxury hotels.

We wanted to find the right site and really focus on that. There were a few starts and stops. At a time, we were first supposed to do a project called the Downtown Athletic Club, which is in the Wall Street area and known mostly for giving out the Heisman Trophy, and that ended up being… We bought it and sold it. Then we were going to do The Hudson, and we thought we were taking that. Somehow there was a back door that Ian Schrager somehow was able to do it. In the disappointment of not being able to execute that deal, we went for lunch in SoHo and we parked at a parking garage. Across the street, there was a for-sale sign on a little metal workshop on Thompson Street that said, “For sale by owner.” I called up, and we bought it. That became the site for 60 Thompson. It evolved from an intimate, more of an inn to something a bit bigger and in concept more bigger, something a little stronger. It was very early in the evolution of lifestyle hotels at the time.

SSR: What year is this?

JP: You’re talking 1999 when we bought it. The Mercer wasn’t open yet. The SoHo Grand wasn’t open yet, or it was just about to open. There was no W Hotels. This was very early on. We opened it with somewhat modest expectations of just doing something, and we learned a lot along the way. We brought on a designer named Thomas O’Brien from Aero Studios was starting to evolve and partnered with Jean Marc Houmard and his team from Indochine for food and beverage. We put together a very strong team, but I don’t think we ever had a vision that this was going to become an international brand. We opened right before 9/11, literally our opening party was on September 10th, 2001.

SSR: Oh boy.

JP: We had this crazy party with British magazine and all these celebrities were there. I was like, “Wow, I could do this. This is fun.” The next day was 9/11. It was a horrible struggle for a few months, but ultimately the hotel resonated, and it was a big success, thankfully. From that was born others. We decided to develop more, and we did one on… Other funds and developers came to us and said, “Hey, I want you to do this for me.” That’s the first time we thought about being a brand and a national management company and building this engine.

Within a few years, we went from one project to 13 or 14. It was a big growth spurt, and then there were various other… We merged with another company and then sold part of the company to Hyatt. It got big-business complicated later on, but along the way, the opportunity… I’m very fortunate to have worked on some really amazing projects, stuff that was industry-changing, and it’s that fabric of the total arc of the… That time period, when I look back on it, has made me… I think it’s interesting as to what foundation it built for the next chapter.

SSR: Yeah. Was there one of the hotels that really stands out in your mind as one of these amazing projects or that was really what you wanted Thompson to be? I know it’s hard to pick your favorite child, but is there one that you want to talk about that you think really defined what Thompson should be and was?

JP: The first one obviously resonated because that started the brand. I think what probably I’m most proud of is today, that hotel’s opened 20 years, and it’s still on the tip of the spear of lifestyle hotels globally as far as nightlife, as far as where it’s rated from a room product, from service culture, from aesthetic. That’s what I often say to people in the industry. It’s like, “It’s not that hard to be the hot place for six months, but talk to me after 20 years if you’re the hot place, and then we’ll see how great your decisions were at the time.” There’s been a lot of hotels that have burned hot and short in that period.

I think that’s probably what I’m most proud of, of the career, but I think there were a lot of firsts. I think we were really early to go to Hollywood and create The Roosevelt, which was this chaotic… I’m not sure it was what we envisioned Thompson to be, but it was its own animal. I definitely did not anticipate that it was going to become this global phenomenon as it had when I went. I showed up there. I was, I don’t know, 29, and I was just thinking I knew what I was doing. All of a sudden, it’s this crazy convergence of celebrity and LA and glamor. That was an incredible experience.

I think it was great to do our first international project in Toronto. I think The Beekman was an amazing building to… Once in your career do you ever get to restore a building like The Beekman. A lot of people could do that extremely badly. There was a lot of pressure to do that well. I’m very proud that that came out. Even though it’s not one of our collection anymore, I’m proud that it held true. I think our first hotel in London, in Europe was very exciting. Mexico, doing Cabo as our first resort was exciting. There were so many pioneering moments as a hotelier that you get to keep moving forward and doing new things. You’re not just doing the same thing.

I’m not so sure that any independent brand could start today and do that much and still have it be groundbreaking in each step. I’m not sure that the industry is accepting of that anymore, and it may be just be too much. I think that’s how the industry is changing. The industry is a little jaded. With each opening, the public and the media is looking for some value proposition that’s different than what so many other brands are doing. Early on, everything you were doing was groundbreaking. Any hotel I opened, I had four pages in W or Vanity Fair or da-da-da just because it was such an exciting time and so different to do the kind of things that we were doing.

SSR: Do you think part of this jadedness and competitiveness is due to the crowdedness of the marketplace today?

JP: For sure. Look, what happened was in about 2008, in boardrooms across the country, in Hilton and Marriott and various other companies, they said, “If guys like the Pomeranc brothers from Queens, New York can figure out how to do all of this, we have to be able to figure it out.” They threw a tremendous amount of energy and capital into trying to capture the lifestyle sector. You have growth of W, of Indigo, of EDITION, of… I can go on and on. Some of those are better executions than others. Some of the internally-born brands did not succeed as opposed to the ones that were acquired by acquisition, but there’s just a lot of value. If you wanted to have this type of experience, you had a limited number of offerings in a major city. Now you have many, many more. Saturation is part of it, but also everything else has changed. Technology has changed. The way people travel, what they consider luxury has changed. You have to be able to evolve. How people find hotels and brand loyalty and how that’s acquired is very different today than it was even 10 years ago.

SSR: Yeah, for sure. You’re saying to have the Thompson in SoHo for 20 years, how have you evolved it? Because you can’t just stay status quo. You constantly have to tweak, not totally change, but tweak. But has that been part of your… I know you’ve rethought F&B and your rooftop and different partners. Do you think that’s part of your success is that you haven’t sat on your laurels and you’re always trying to continue to improve or rethink, especially with how things have changed over two decades?

JP: I think that’s part of it. I think a great hotel over time is very much like a stately home. If you have this incredible turn-of-the-century mansion, and you buy it in its original condition and you need to restore it or whatever, you don’t just rip it out and in the ’80s put a bunch of formica in and then in the early 2000s put a bunch of black lacquer and then… You evolve stages of it. A stately home has components of each period that it goes through, and it moves. I think hotels are very much the same. That’s on the physical side.

That way, your design and your aesthetic becomes somewhat timeless, and you don’t become locked in a time capsule. Look, one of the reasons I was so enamored by the hotel business is I walked into some of the early Ian Schrager hotels, like the Delano, and you were getting punched in the stomach because it was like, “Wow, what is this? What is this Philippe Starck kind of craziness?” But to an extent, that became a prisoner later on in that career. As great as it is, over time, people’s taste changed, and it didn’t fit. Turning that into the next version of that became challenging. I think it’s hard for any successful aesthetic to evolve. I think that’s why today some of the most successful hotels cannot be pigeonholed into a design description.

They’re mostly eclectic because there are various periods. Some is vintage, some is new color, not color. It becomes very personalized, and that’s very much in an effort not to become dated quickly. I think that’s on the physical side, but you definitely need to evolve your offerings. You’re changing your service culture. You’re changing your F&B offerings. We, at a certain point, took two of the most popular places in New York, and we just had to change the concept because we just thought that they ran their course. Instead of having a Thai restaurant, we had a French restaurant. Instead of having a hotel bar, we decided go into this art-field border between nightlife and lounge. Sometimes you have to tweak again. It doesn’t always work exactly the first time. It’s very organic, and it’s painful.

I often tell this to people in the business, “Why do you have to make it so hard?” because you want to do a collab with this different company, and they’re not prepared, because if it’s not painful, that means it’s just not… If it’s that easy, it’s probably not that good. I know that sounds ignorant, but the creative process is inherently painful. If you want to take that extra step, you have to be willing to put into work. You have to be willing to deal with eccentric personalities. It’s not regimented in a boardroom format. That’s why even today independents can still create product that stands above what I think the larger corporations can because they’re willing to take that extra mile. Things are not decided by a committee. I often say that this business from our end is 80% traditional hotel, economics, service culture, what you learned in hotel school, but 20% is voodoo. It’s completely subjective. It’s completely out there. You can go right, or you could go wrong, and it often comes down to one person’s perspective as to where culture is moving. That is a risky proposition

The Civilian; photo by Johnny Miller

SSR: For sure. Is there one part of the process you like the best? Is it finding the spot? Is it that initial concept? Is it seeing it come to life?

JP: The early stages are the most exciting clearly because you have limitless detention. All the ideas are possible. Once you’re in the heat of construction and building, everything becomes a bit more realistic and a bit more harsh, but the white paper stage… because I approach projects very cinematically. Let’s just say we’re looking at a piece of property or an old building. I don’t see the whole project. I see a very, very tight scene, almost like a movie that pans out. You see one little corner, and then everything else starts to fill in. That’s the part that gets my juices going. That’s the exciting part.

Look, I like dealing with eccentric, creative personalities. I often say, when I’m dealing with institutional investors and funds, is, “My chief skill is a little crazy into corporate America.” I’m the bridge that makes that all work, but you need that. You need that. You can’t sanitize everything to the point… Otherwise, I think the guests can sense that. I think we lose our opportunity to be mirrors of cultural progression. You know what I mean? Because what happens is often with the more corporate-driven hotels, you’re looking in the rear-view mirror of what culture is doing. I think as an individual hoteliers, we’re creating or help perfecting where it’s going to go. I think that is the major difference.

SSR: Yeah. You’ve worked with amazing people, you said, like Studio Collective, Tara Bernerd, Martin Brzezinski. I could keep going on and on.

JP: Sure.

SSR: What do you look for in a collaborator, and what do you think makes for a successful collaboration where you can create this magic that you’ve been able to create?

JP: Well, clearly… because great designers don’t mean that they’re great for a specific project. It’s not one-size-fits-all. They’re human, and they have perspective, and they have a taste level, and they have background. Certain projects are better suited for a certain type of design firm, but even one you are there… Look, I think as a client, for me, the openness to collaboration is very important. It’s not something where I want a presentation and say, “Okay, I want A, B, C,” and, “Goodbye,” but it’s also passion. If I sense that a designer is not excited about this particular project, I’d rather find an unknown that is looking to prove themselves and has a skillset and take a risk on them and do it, because passion is… and going back and looking at it again.

Some of the best discussions we’ve had over the years have been about one detail, that you get into an argument of, “No, I want it to be this. I want it to be a beveled edge.” You get into these crazy discussions about tiny things, but you need that passion in order to have the project be great. I think that’s probably the most important thing to me. Even today as I talk, and I’m always trying to find who the next person is going to be or the next firm is going to be… That’s what I look for the most. It’s funny. I also like to see someone that says, “I have a distinct perspective and style, but I really like and respect what A, B, and C are doing.”

I’m the same way with food and beverage too. Some people become so myopic that it’s like only what they’re doing is right. I’m not like that as a hotelier. I love to go to other people’s hotels. I like to see what they’re doing. People often see me in a restaurant or in a bar in somebody else’s hotel. They’re like, “Why are you here?” I’m like, “What do you mean why am I here? I’m here because I want to have a good time and I want to see what’s going on. I know how hard this is to do, so I appreciate that.” In my mind, there’s a real esprit de corps that should happen amongst the individuals in the industry. We should all be helping each other meet that challenge. It’s not always that way. I think I’m maybe unique in that perspective, but I enjoy seeing other people push the boundary a little bit.

SSR: Yeah. Has there been one very memorable hospitality experience for you, either as a kid or later in life, that has stuck with you?

JP: I think traveling to Asia the first time and just really experiencing it as a different planet in its aesthetic, in its service culture, in its landscape. I had the opportunity to bop around into different parts and cities and remote areas. I think anybody in hospitality, and certainly anybody on the design end of hospitality, needs to experience that depth. You can say the same about Europe too, but I take that a little for granted because there’s more of a synergy between the US and Western Europe, but Asia is a different planet, and it’s really eye opening.

SSR: Is there is travel wish on your bucket list that you haven’t gotten to yet?

JP: Well, right before COVID I was supposed to take a deep-dive into Japan. I had a three-week, extensive, heavy-duty Japanese trip planned starting in Tokyo and going around the country. That’s as soon as things get back to a normal. A little trickier now with my baby, but that would be probably first and foremost. I’m embarrassed to say I have not yet been to Japan. I’ve had a few few starts and stops, but that’s high on the list.

SSR: That would be amazing. All right. Let’s talk about your newest endeavor and what you’re up to with CIVILIAN Hotels and the first… Is it going to be a brand? First of all, I should ask that before I ask the next question.

JP: Well, if it’s successful, it’ll be a brand. If it’s not, then…

SSR: Then it’s a one-off, and it’s great.

JP: Right. Yeah. Exactly. I say that about most hotels. It would be nice to be a brand, but you’ve got to actually prove the first one. I love it when I see presentations of brands that have 21 locations pegged on a map, but have no hotels open. I’m like, “Okay. Let’s talk in a few years from now and see how many of those come to fruition.” But it is meant to be a brand. I think it was conceived. If you recall, I concepted what’s now Tommie and Arlo. I’ve been playing with the high-end, limited-service space… smaller-room, high-design, deep public-space concepts in a while. I think CIVILIAN’s going to be 2.0 of that. Our goal is to provide accessible luxury for a more youthful consumer, and creating petite rooms, but really of the finish almost of what you would have in a traditional lifestyle hotel, and same with the public spaces.

JP: It’s one step in the ascension into the luxury market. I think that’s an area where there’s a lot of room for growth in the hotel world. I find that exciting, and I think it’s a good place for a beta to be in New York City. In the future, I have different concepts of different components I want to integrate when I have a little bit more spatial room of public space, of coworking components and other things. I think technology’s playing a part in this and the check-in procedure and booking procedure and communication. It’s also reinterpreting what the guest experience looks like. We’re giving guests the opportunity to decide what’s most important to them when they book, “Is it the basic-room experience? Is it a slightly elevated one? How much housekeeping? Do you want a mini bar drop? What is it that you care about?” and using slightly almost an airline model but more personalized in providing a very clear distinction within the same framework of how you can curate your own experience.

I think that’s exciting. It’ll evolve as the space is opened and as we go into 2.0 and as the tech keeps changing, but that’s where the future is. I think the future in the kinds of hotels that you cover and we talk about is in two places. I think it’s in the real luxury market, and I think it’s in this reinterpreted accessible luxury market that’s going to replace a lot of the flag, mid-price concepts, like Marriott Courtyards and things like that, because at that price point, we can give a better experience to guests. You’re seeing it already with some of the other brands. Moxy’s in that space a little bit, and some other brands. But we do think that that’s probably the territory globally that needs the most product. Whereas the four-star, four-and-a-half-star product is quite crowded, super luxe and this accessible luxury, mid-price market is the best place to be.

SSR: Hospitality is always known to be behind the times with technology. How are you trying to stay ahead of it? It’s very mobile check-in. Like you said, everyone gets to choose everything, which is super exciting and almost like that airline model, but is it a big learning curve to bring it in? Was that hard to get set up, or do you think it’s easier now? Because I like feel hotels take, what, five years to get built, and by the time you start, you’re already behind. I don’t know. I’m just curious about-

JP: Well, hotels are notoriously slow to adapt technology compared to other sectors. E-commerce and retail is just so far ahead of where hotels are. Part of that’s an integration issue. Part of that is a fear issue of taking away the personalization with verbal communication. But I think it’s getting there. I think the reason why it’s getting there is not because the hotels are on the forefront. It’s because the consumers operate that way. That’s how they do everything else. Between Amazon and online shopping and their air travel, they’re getting used to this dexterity using mobile devices and technology, whereas… They want it. They think it’s archaic to have to go to a desk and check out of a hotel and spend however many minutes when you’re late just to tell people that you’re leaving. It’s ridiculous at this point a little bit. The guest is driving that desire to be more flexible.

SSR: Yep. Why was this the right hotel? I know you wanted something in New York… or New York is the right market to test this in, but tell us a little bit about CIVILIAN, its location, and what you, in collaborating with David Rockwell, created for the city.

JP: When I started the project, I said I wanted the brand to represent the democracy of style. I want it to become a very all-inclusive product that different sectors of people could really appreciate at the same time. Whereas previously, I wouldn’t say that my other hotels were exclusionary, but they were very hyper-focused on a particular market. Whether it was fashion or entertainment, or depending on where it was, we really focused. What I wanted to do here was provide a product that, first of all, even though it was geared towards young people, it was marketed towards young people, really, anyone would feel comfortable staying. I do think the psychology of the consumer is inherently young at the moment anyway. You market towards youth. Whether you’re not, you’re 50s or 60s, or whether you’re in your 20s and 30s, you’re kind of marketing the same way.

I thought that the juxtaposition of being between Hell’s Kitchen and the Theater District and the revitalization of New York created the greatest opportunity for a mass audience of all kind… from the Dutch backpacker to the couple from the Midwest that wants to see Broadway to the LBGTQ community that is gravitating a lot towards Hell’s Kitchen, creatives that are from the music industry that are in Times Square. It just was a wide breadth. I think it was a great place to be a beta for this brand concept. It was great to work with David. I think one of the things that David brought to the table and opened my eyes to was…

I’ve had the opportunity to immerse myself in the entertainment industry and the fashion world because of other projects. I’ve never had the opportunity to immerse myself in the theater world. He’s really been the conduit to bringing that culture into this particular location. I’ve always liked my hotels to be hyper local in its voice, particularly in the public spaces to the guests, and I think bringing in the theater community, bringing in the art collection from really, really interesting, and I think unique, and I think just as a spectacle provides a lot of value, as opposed to just doing a nice hotel, had been immensely useful and very educational to me because I find it fascinating.

It’s exciting to me to say, “You know what? Maybe we can provide the new go-to place for that community in the way that Joe Allen’s used to be and some of the other spots of the ’60s and ’70s. We could do it for the next gen because Broadway’s changing too. You’ve got your Dear Evan Hansens and you’ve got your Hamiltons. There’s components of crossover between traditional music industry and film. There’s a lot of intellectual capital to mine there to create a better experience for the guest.

SSR: Yeah. I know you don’t want to have a list of 21 places that you’re moving the brand to, but if this is successful and you do continue CIVILIANs, do you see them in other major markets? Are you looking at other second or third-tier markets? Where would you in a perfect world-

JP: Well, I do think it’s a city prop. I think it’s a city hotel. For that, I’m going to say major cities with a caveat. Major cities today are very different than they were 10 years ago. Major cities in the US were three, two, actually, two and a half. Now it’s a plethora of interesting places that young people are moving, the tech industry is moving to, and so there’s a lot of cities that were not on the lifestyle map maybe a decade ago that are today, and I think hopefully ultimately internationally in a few cities as well. I don’t want to get too ahead of myself. We’re negotiating one or two other locations now. Look, you build a brand one by one, and then all of a sudden, it explodes. But right now, it’s about making this one work and then potentially the next one. Then those are building blocks, and then everything grows from there.

SSR: Yeah. You’ve built so many things along your career. How is it to go through this process again?

JP: It’s great.

When I was interviewing, actually, Ian Schrager for the guest-edited of that I did a few years ago, I asked him… I’m like, “Do you still get excited about what you’re doing? What do you think?” He’s like, “Look, it’s what I love to do. I don’t love to play golf. This is my passion. I like the challenge of having to reinvent myself. I like the challenge of being in the trenches.” It really made me feel not like an oddball for just being like, “Look, this is what I like to do.” I’m not sure exactly where the path is going to go, but it’s going to go forward, and at whatever pace or speed or direction it may evolve over time. But at the end of the day, I’m of a certain breed that loves what they do. I take the negative parts of it in stride. I think that everything I’ve done until now is just one chapter. I think the next chapter, and I put this challenge on myself a little bit… Hopefully it outshine the first one, but it should at least be the natural progression from the first one.

SSR: Yeah. You mentioned this lower tier that you’re working on and then the ultra luxury that you think is ripe for development. What do you see as that definition of luxury? What do you think is missing, or where do you think that is evolving to, that ultra luxury right now?

JP: Look, luxury’s changing all the time. I think it’s been like that probably for the last few years where you’ve seen some individual hotels take the rate leadership and the luxury definition in certain markets, and now you’re seeing some of the traditional luxury chains follow suit. If you look at some of the new Four Seasons, they’re bringing in designers that came from the lifestyle world and they’re bringing in branded food and beverage components. They’re all taking cues from that world. But at its core, luxury is just more casual. I think people want control over their environment. I think they want less of a sanitized script in its service culture. I think they want more flexibility. In a certain way, you’re taking more cues from the residential community.

JP: They want to think, whether if it’s in New York, that they’re staying in their great SoHo loft, or if it’s in Miami, that they’re staying in the equivalent of that on the beach. I think they want to take some of the formality out of the traditional luxury. I think they want a more innovative and tasteful aesthetic, and to end the traditional room-cube aesthetic that the luxury chains have been using for a very long time, and rethinking locations as well. In New York City, you’ve got a Ritz Reserve opening in NoMad, which never would’ve happened 10 years ago. You have a Four Seasons in Surfside in Miami. I think globally, when you look at what Cheval Blanc and Belmont and Rosewood… They’re trying to move outside the box a little bit, and I think that’s exciting.

But there’s also room for the individual to still have an ownership there and create something that pushes the boundaries, and particularly in resort environments and remote locations. I think COVID pushed the world to really appreciate drive-time remote locations, but also relatively accessible travel to whether it be the Caribbean or whether it be Mexico, that is really immersive, whether it’s beach or whether it’s mountain. You’re going to see tremendous growth in experiential luxury that way. You’re seeing it from the change with trains, and you’re seeing it with more Upstate New York, with more things happening. You’ll see the same in Northern California. You’ll see this model of these remote locations becoming quite active. Part of that, when you get into the business side of it, is there’s going to be a residential component layered into that.

That’s going to be a big thing, where your second or your third home is going to be a part of some kind of compound of luxury resort. That’s, I think, where the business of luxury is going. Plus, I think when you look at brands like Soho House, which are not traditional luxury, but I think they’re doing an interesting job of branching into other lifestyle areas like furniture and accessories and things that really translate hospitality into your home, which I think other brands are going to follow suit, which is great because we all want to take a little bit of that special experience home with us. I’m not sure we want to design our homes exactly like the hotel room we stayed in or the lobby we were just in, but one piece of it is interesting and gives another aspect to how these brands can set their reach out, because it’s not going to be, “Hey, I’m acquiring enough points. Therefore, I’m going to stay at this place.” It’s going to be, “I want to feel connectivity to this lifestyle.”

SSR: Okay. I know your homes have been featured in many publications, but are they similar to your hotels or very different?

JP: I think there are components of it, for sure. A lot of stuff that I did for my homes started in 1950s, ’60s, and early ’70s iconic furniture designers and architects. I think while some of the hotels don’t necessarily translate that as literally, there’s definitely components of that color palette, of certain iconic furniture pieces that I think are just wonderful to have in any environment. There’s a lot to be learned from that. But then again, there are other projects that I’ve done, like Beekman, that were more turn of the century into the 1920s, and yet there were components of and other period designers that haven’t been in my home. I think the process of breaking it down is very much… Using my homes as a lab to do that is very much useful in the commercial projects.

SSR: Very cool. What’s one thing-

JP: And less expensive to experiment because it becomes my problem, right?

SSR: On a smaller scale versus a massive lobby.

JP: Right.

SSR: What’s one thing that people might not know about you?

JP: One thing that people might not know about me? I’m fairly an open book. I’ll tell you a couple things I shouldn’t be saying. One is despite my putting myself out there as a somewhat of a culinary expert and telling people these exotic sushi dishes to order, I actually have the palate of a 12-year-old boy. I eat pretty much like your kids probably do for the most part. That’s one thing. Though I can appreciate music a lot, I don’t dance at all. When I was a young man going to club for the first time, there was a very famous nightclub guy in New York, and I’ll leave his name out of it. He pulled me aside because he thought I had a future in this business.

JP: He said, “Let me tell you something, we don’t dance. We act as if we don’t even hear the music. We have perfect conversations as if the music is just going on.” Now, that is completely not any kind of advice I would give anybody today because it’s silly, but it just got slammed into my head as that was the cool thing to do as a teenager. I have not been able to get out of that rhythm. Maybe as part of my next evolution, I will take some flamenco or something just to break out of that mode.

SSR: Yeah. Or at least a little sway, something?

JP: Well, yeah, the banquette sway comes with the territory, but we need something with a little more flamboyance.

SSR: Yeah, exactly. Add that to your next chapter. I love it.

JP: Right.

SSR: Okay. I could talk to you forever, but for the sake of time, we always end this pod with the title of the podcast. What has been your greatest lesson or lessons learned along the way?

JP: I think there’s a lot. It’s hard to say. Look, in the end, it’s a business with very sharp elbows. I think you talk about the aesthetic portion of it, but to really go for someone who’s really entering it and saying, “Hey, I want to accomplish something,” whether it’s in the restaurant field or in the hotel field, “from scratch,” it is a hard business. It is fused with all of the components that make people act aggressively, money, ego, a degree of fame. There’s an underlying current of sexuality to it. What makes it exciting is what makes it explosive.

JP: My take on it is I wouldn’t change anything and have done anything different, but you don’t go into it being naive, but, and at the same time, temper that pessimism with real passion for the stuff that we’re talking about, about brand and about aesthetic, because in the end, you have to keep your artistic integrity and balance it with your business plan, because if you don’t, you’ll just hate what you’re doing. The things that I have regretted in my career have always been when I’ve compromised too much to appease the situation and it wasn’t the best it could be, or at least it wasn’t my subjective vision of the best it could be. I think, “Hold true to your vision, but be prepared for a rocky road.”

SSR: Yeah. Awesome. Well, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me today. It was so good to see you.

JP: My pleasure.