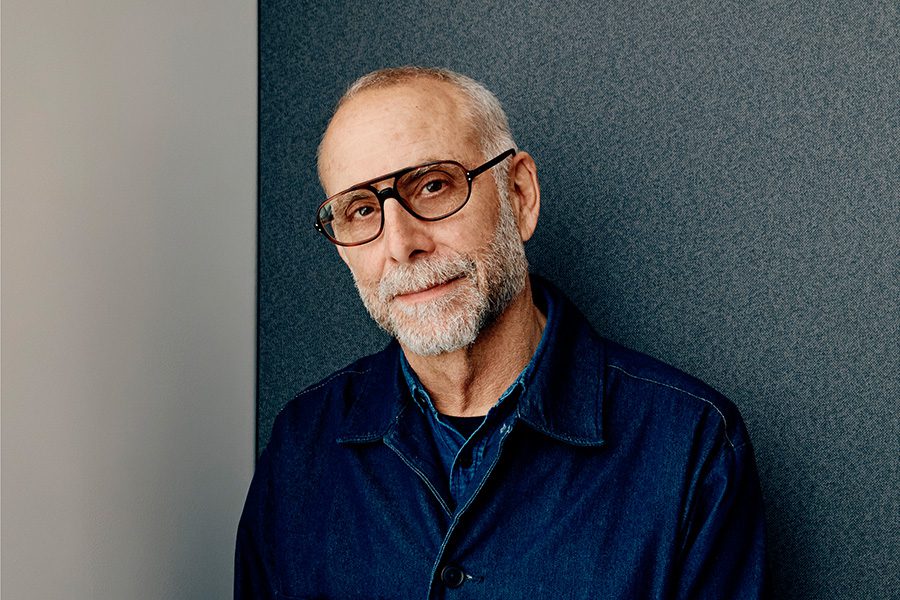

Morris Adjmi

This episode is brought to you by American Leather. For more information, go to americanleather.com.

Details

As founder of his eponymous New York firm, visionary architect Morris Adjmi’s work is deeply rooted in a respect for heritage while embracing innovation. With a career shaped by early experiences working alongside Pritzker Prize-winning architect Aldo Rossi, Adjmi developed a distinct approach that balances modern aesthetics anchored in a deep understanding of architectural and cultural history.

His projects, spanning adaptive reuse to new construction, reflect a meticulous attention to detail. Take the recently opened Forth Atlanta, which is revitalizing the Georgia city’s Old Fourth Ward with Adjmi’s signature refined yet curated style.

Adjmi’s forthcoming projects—including the renovation of the Swan Hotel at Disney World in Orlando, Florida and the Four Seasons Hotel Charleston in South Carolina—maintain a dialogue between past and future to honor each city’s identity while reimagining its possibilities.

Subscribe:

Stacy Shoemaker Rauen: Hi, I’m here with Morris Adjmi. Morris, thanks so much for joining me today. How are you?

Morris Adjmi: I’m great. Thanks for the invitation. Really happy to be here.

SSR: Well, we’re happy to have you. So we always start at the beginning. Where did you grow up?

MA: I grew up in New Orleans.

SSR: I don’t know if I knew that. Maybe I did. What was that like?

MA: It was great. I love New Orleans. I still have a house there in the Garden District. I spend a fair amount of time down there. And I sort of credit New Orleans with making me who I am.

SSR: Yeah. What were you like as a kid?

MA: I was pretty creative, rambunctious. The earliest memory I have, I was probably about 5 or 6 of being an architect or a builder, was I constructed a pyramid in the center of the living room out of coffee tables and side tables trying to reach the ceiling. And just as I was about to reach the ceiling, the front door opens, my mother came in and the whole thing collapsed. So I cut myself and I had to get stitches and all that. But yeah, I was always getting into things.

The lobby at the Forth Atlanta; photo by Matthew Williams

SSR: Yeah. Was your mom or dad in the creative field at all, or anyone around you?

MA: Not really. I sort of came out of nowhere, I guess. But really inspired by the city. I mean, New Orleans is obviously known for food and music and architecture. And just having all that around, I think influenced the way I looked at the world and what really stimulates me.

SSR: Yeah. Did you end up going to college for architecture or design?

MA: I did. I did. I graduated from Tulane. I got a master’s from Tulane. About three years in, I was studying architecture from the beginning, I decided that it was time for me to leave New Orleans, so I did an independent study program at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, and that’s where I met Aldo Rossi. And that really, I think, was a pivotal moment for me, just changing my perspective, but also opening a lot of new opportunities.

SSR: Yeah. And what was it like working with Aldo?

MA: I think it was the one most dramatic event or change in my life was that experience. And in addition to really watching a genius at work and seeing the design process and seeing how things came together, just also having the experience of watching how he dealt with clients or decisions about his career or the profession informed how I do the same, if that makes sense.

SSR: Yeah, no, totally. And did you live in Italy then, working with him?

MA: I did. And I studied for a year in New York, and then I was traveling the following summer through Europe and stopped in Milan. And he had asked if I could help with a competition for a housing block in Berlin. And then the office won the competition and then asked me to come back and stay. And then I worked on an opera house competition in Genoa, which they also won. So yeah, that was amazing. I mean, the experience in Italy, as I said earlier, my experience growing up in New Orleans was sort of pivotal in my appreciation for architecture, but I think working with Aldo and then also seeing how things were built or how cities were made post-war Milan rebuilt in a way that I think is how we look at architecture.

SSR: Yeah. And what made you decide to go out on your own? And that was in, what, 1997?

MA: Yeah. Well, Aldo had called me in, say, ’85, ’86, and said he wanted to open office in New York. Because I’d been back for a few years and we opened the office. And then he died in a car accident in ’97. So I, at that time, finished the projects. We had four projects, a project in Japan, a project in California, one in Florida, and the Scholastic building in New York. And so I had committed to finishing those projects with all of our clients. And so took all those through and then at that time started to open my own office as an offshoot of the work that we were doing.

SSR: Yeah. Got it. I mean, let’s talk about some of those projects. What do you think was the most challenging or memorable, however you want to take it, project that you worked on for Aldo?

MA: Well, I think there were a couple of projects that were key. And since we are interested in hospitality, we’ll go there. So I would say that the most important project. There were two, I’d say two projects working with him. One was a hotel Il Palazzo in Fukuoka, Japan. First really, I think, as recognized as the first boutique hotel in Japan. Working with a number of very talented interior designers. Shigeru Uchida invited Aldo to do that project. And then Koremata did one of the bars, Sotsus did one of the bars, Itano Peche did one of the bars, and we did one of the bars, and Uchida did all of the interiors for the hotel. But that project really was important, I think, for the office, also for the city. It really transformed Fukuoka into a city that really focused on design and invited a whole host of other very well-known architects to do work there. So it was really about city building, but also placemaking.

SSR: Was that your first hotel or you worked on others before?

MA: That was the first hotel. And that was finished in ’89. And then the other project that was, I think, key to sort of setting the stage for how we look at context and history, and the combination, was a Scholastic building in Soho, which was at that time the first new building in that cast iron historic district. And just really understanding context. It was Broadway. It was a thru-block with one face on Broadway and another one on Mercer. And it recalled the way cast iron buildings were put together, but it was a modern building. It was very, I think, appropriate in terms of the way it looked at the street scape, looked at the history of cast iron, and also as a building for the children’s book publisher, Scholastic.

We had had a pretty generic facade on Mercer, which was the back facade. And the Friday before we presented the project to the Landmarks Commission, Aldo was in town and he’s like, “I really don’t feel good about this facade.” And so he started sketching and sketching, and I still have the drawings. And he’s like, “What do you think?” And I’m like, “Aldo, I think it’s fantastic, but we have to present this in two days.” He goes, “Well, I think we shouldn’t present the other one, I think we should present this.”

And so I called Bill Higgins from Higgins and Quasebarth, they were the landmarks consultants, on a Friday, literally at 5 o’clock, at the end of the day, and I was like, “Bill.” And he was in the office, which I was happy, I said, “I think you should come down to my office. You got to look at what Aldo’s working on.” And so he came. I said, “Well, what do you think?” And he goes, “I think we should do it.” And so we worked over the weekend, we changed the whole presentation, and that’s the design that you see. And that’s like one of those things that I said I learned from Aldo, it was like, if something’s not right, you have to do the right thing. And that’s what we did. It was just drawings before that. And once it’s a building, it’s too late. Luckily, he had the foresight and the will to make the best building.

The Pinch Charleston, a concept from Method Co.; photo by Matthew Williams

SSR: I love it. What did he change it to? Now I’m curious.

MA: It was sort of, when I say it was generic, it kind of was like the front is very almost like mannerist. It has these big columns and beams and it recalls what you’d see on a cast iron building on steroids, I’d say. The back facade was just like this generic, almost like a curtain wall or something. And so then he put in these big, sort of industrial arches, organized it like a three-part type construction stacked up, and it really made a difference.

SSR: Yeah, I love it. Okay, so he passed away, unfortunately. You took on the last couple of projects. Did you have a big team or did you have to rebuild, and what was it like changing from an Aldo Rossi to Morris Adjmi?

MA: I mean, it was an evolution more than a revolution, because sort of this idea of looking at context, looking at history and building on that, that was sort of Aldo’s way, looking at the big picture. Also, if you look at the Italian design, whether it’s furniture or architecture, there’s an element of tradition and an element of innovation. And that’s how there’s this continuity, but it’s always progressing. And I think that’s what I saw in the city of Milan, where buildings were called the historic buildings. There was a lot of infill after the war, the buildings that had been bombed, but it still felt like it was the same city as opposed to all of these big statements that kind of are competing. And so that transition is sort of the way I built the firm.

I would say the biggest difference was that Aldo was an architect and that was kind of his position, and I’ve built the firm to be more multidisciplinary. So really bringing in interior designers. Trying to use the same narrative-based, contextual-based, historical-based approach, but to overlay a real interior focus point of view as opposed to an architect trying to do interiors. And I think there’s a very big difference, and it’s important to have both if you want to do successful projects.

And then that’s also grown that we do placemaking and planning. And we started an art program in the office about 11, 12 years ago, that we inaugurated with a collection of the drawings that I had from Aldo, and that’s grown over the years. And that’s turned into a service that we are providing our clients with, where we’re selecting the art so we can do everything from the big picture down to selecting the art that goes into the projects, which we did at Fourth. And so that’s kind of this holistic design, is I think a little bit of a different point of view. I mean, Aldo was doing desktop, whether for Alessi or furniture for Moltani, but it was sort of separate, and this is kind of more of a holistic approach.

SSR: Right. So one informs the other and you feed off of each other.

MA: Absolutely. Absolutely. And it’s good to shift scales, go from city to a living room.

SSR: Yeah. And you mentioned it briefly, but talk about your process for projects. You talked about the context and the history and really weaving in where it is, but what does that look like to you and how do you start each project?

MA: Yeah. I think that has come out of, again, that whole story of the Scholastic experience, really trying to create a storyline, a narrative of what’s driving the project. And that enables us to make decisions about what feels right, what’s appropriate, and specific materials we might choose or design moves that we might make. It feels like you can create this story. Then if it’s true to that story, then it works. And I think we do that on the interiors too, really understanding what’s the message and what’s this. So it’s a conversation, we say conversation-based design, and it’s a conversation might be with history or might be with the context, or might be with what the messaging is for the particular client or user.

SSR: What’s the biggest challenge running your own firm and what is the biggest opportunity you think today?

MA: Wow. Challenge, everything. I think getting good people, I mean, that’s always a challenge, and I think that that’s what makes an office successful is having a good team. And so I think we’re very focused on having a really great working environment. I think coming off of Covid, where we were a hundred percent remote, coming back, and I’ve been originally trying to balance between virtual and in-person, and trying to lean into the in-person analog experience being a better experience. We were having these hybrid meetings where you have half the team or three-quarters of the team in the room, and then a couple of people on the screen, and it’s just we ended up trying to explain to them what we were doing. It’s been a challenge a little bit, because obviously everybody likes to have flexibility and freedom. But you can do more in five minutes in person than it takes to do an hour on a call.

And in some ways I’m really happy because I’m not flying all over the place and doing some Zoom meetings, but really, I flew out literally for 12 hours to LA last week, and that meeting was so much more productive than if we had done it on a call. So yeah, so that is a little bit of a challenge, but I think we’re leaning more and more… We’re back four days a week now, and I see five days coming soon. That’s not going to be everybody’s happy place though.

SSR: How big is your team now?

MA: We’re about 75 people. About 25 on the interior side and a few people on the sort of planning side, a few people on art services, and the rest architects.

SSR: Got it. And how are you trying to build back this culture too, to get people into the office?

MA: I had a conference room table. I have my own conference room. We have a lot of conference room. My own conference room. And I literally took the furniture out of my conference room, put it in the middle of the office, and we do all the meetings, all the work design sessions outside, so everybody can feel like they’re part of that process. We pin up a lot now, trying to get away from digital. So we’re sketching and drawing, we can pull things up, but trying to make it really analog. Taking tracing paper out, sketching, and really being hands-on.

A rendering of the forthcoming Four Seasons Hotel Charleston in South Carolina; rendering courtesy of MA

SSR: Yep. Oh, I love that. So what do you think or how do you think this multidisciplinary approach really helps your team? I know you touched on it, but do people get to kind of bounce around? Do you bring everyone to the table for these conversations? I mean, in an ideal setting.

MA: I think there’s always been a tension between architects and interior designers, and that’s one of the reasons why I felt it was important to bring it together. We worked on a project where they brought in another interior designer, and it was like you came through the front door and you’re like, I could be anywhere. There was no connection between the architecture and the interiors. That doesn’t mean that one should be subservient to the other, but they should row in the same direction and they should play nice. And we’ve tried to blur the lines and bring the teams together.

We usually have an interior designer at even the earliest meetings on the architecture, and vice versa, so we’re not starting from scratch when we start to look at the interiors. And we look from the outside in and from the inside out. And so I think that there’s a big benefit to doing that. And the way that that happens is not necessarily the same in every project, but there is a connection, and I think that’s the important part. But it doesn’t matter if it’s the materials are coming from outside in or the thinking about an arch or motifs in the details, but there is something that does connect the two. And I think that’s how you make great buildings, when you connect all of those pieces.

SSR: Yeah. And speaking of great buildings, you just finished the Forth in Atlanta. Tell us a bit about that project and what you wanted to create for the client and for the city.

MA: Yeah. That, I think, hopefully we created a great place for people to gather, both from the city and outside of the city, and the best hotel and club experience that’s there. And I think it’s gotten a fair amount of attention and it looks great in the skyline. I think the building works as an icon for this neighborhood, Old Forth Ward. And it offers a tremendous amount of public space inside the building for people to come together. And we’ve made some great connections just being there for the opening and different events that have happened there. So I think it’s already starting to do that. We actually hired two filmmakers, two brothers to do a little video for that project, which they’re finishing up now. And it was just a great meeting point, and I think it’s going to continue to foster a lot of great connections.

SSR: Yeah. I know you’re all about materiality, especially in buildings and creating a statement with them. So talk a bit about the Forth. It was one existing building, right? Like a brick building, and then you built this cool tower set almost on top of it?

MA: This was, it was Georgia Power’s parking lot and training center, so it was just a big open field. Jim Irwin from New City hired a number of architects to come together. There was a rough plan that they had in place, and we helped to finesse and massage that plan together. Olson Kundig did the office building, which is about a million square feet of office. Three-quarters of that is built now, there’s another piece that they’ll build soon. We did a residential building with a little over 400 apartments, and then we were hired to do the hotel.

Jim had originally intended to have different architects do every building, but he really liked what we did on the residential project, so he hired us to do the hotel. And so we envisioned the hotel as like a brick building, as you described, on the lower portion. And then this tower, which had a concrete exoskeleton diagrid, diagonal sort of members supporting the hotel from outside on four sides, which is unique because that’s the first time I think it’s been done. And that grid really resonates as something unique and people identify with it. And what we really like about it is that it’s great from the outside and it creates this visual graphic element in the skyline, but also from inside the rooms you see that grid and it creates a different dynamic from different rooms and the view out.

And then on the material side, we really tried to keep the materials really warm and lush. And one thing that we did when we started working with Method, and Method Hospitality has been, I’d say a partner, but we’ve been working with them since they started their brand, ROOST, and now they’ve grown to creating separate individual, sort of bespoke brands for different projects or different hotels. We also did the Pinch with them in Charleston. But this project and all of those other projects, the goal has really been to kind of create an eclectic mix of furniture and materials so that it doesn’t feel cookie cutter and it doesn’t feel like we just went and just bought all the furniture at one place, or did one design that then gets populated throughout the hotel. So all the spaces are sort of crafted and have their own look and feel.

SSR: Yeah. I mean, you did that at The Pinch, too. I mean, the Pinch in Charleston, it feels like a really cool residence almost.

MA: Yeah. And that was like when we started working with Randy and he said ROOST was this extended stay or corporate housing, and he’s like, “I don’t want this to feel like you’re at a hotel or some cookie-cutter property. I want it to feel like you’re staying at a really cool friend’s apartment.” And so it kind of wants to have those layers and that richness of… Some of the furniture is off the shelf, we buy pieces, and then some of it is custom made, but the idea is that it all feels like it’s been collected over time as opposed to one set of furniture that just fills the space.

SSR: Yeah, for sure. So talk a little bit about ROOST, because you’ve done a lot of them. And I feel like they, when you mentioned Randy, Randall Cook of Method, I think they were ahead of their time almost, because Extended Stay continues to grow, right? So can you talk a little bit about that brand and how you interpreted it?

MA: Yeah, so there’s a lot there. And I think that part of it is the overlap where we’re seeing hospitality informing residential projects and the other way around, where residential projects are informing hospitality. So this blend, it’s really, I think, an interesting place to be. And I think where Randy started, where there are apartments, but they’re rented on an extended stay basis or even on a shorter term basis. Randy contacted me, we did the Wythe Hotel in Brooklyn. So he had stayed at the Wythe, he was looking for someone to work with. He had a 27-room project, which was a proof of concept for ROOST. It was the first one, where it was just 27 rooms. And ROOST has sort of grown to have more of a… and as with the rest of the Method brand, to have an f and b component and to have that be in different configurations in different places and inventing different food and beverage locations for each place or in each location, sorry.

We literally were at the beginning stages with him designing the building, but also selecting the product he was going to put in the rooms, the name, the logo, everything. He came into the office and we would have these hours long work sessions. He’d come up from Philly to New York, and we would just look at everything, like, “What do you think about this?” And I think we ended up selecting Davines products. And we liked the bottle, we liked the scents, we liked the fact that they were sustainable products, et cetera, et cetera. And so all those decisions were made together, and we’ve really grown together in the way that we built the projects with him.

SSR: Yeah. And you mentioned the Wythe. I mean, that opened in, what, 2012? I just moved to Brooklyn. Yeah, I just moved to Williamsburg. And it really, it helped change Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I mean, I think it really started the change that that neighborhood has seen over the past, call it 10, 15 years. Talk a little bit about that. Do you think that was one of your big breaks in hospitality? Do you think that maybe put you guys more on the map?

MA: Yeah, I think it’s been a slow growth… Not a slow growth, a steady growth since then, but absolutely. Without that project, we probably wouldn’t be doing the projects we’re doing now. And I think what resonated with that project, first of all, people always take for granted that it is sort of in the middle of everything that’s happening in Williamsburg, but it really was on the edge at one time. I think that we moved the epicenter from 7th and Bedford, to 11th and Wythe. And I think people embraced it because it was authentic. We took an existing building, we shaved a little bit off the side, and we put a new piece on top, but we really leaned into the existing building. We peeled back layers of just, sort of abuse or just junk that had built up on the walls or the floors, but it still felt like it was a real warehouse building.

Amazing materials inside, like the heavy timber construction, the cast iron. We leaned into that. We put a new concrete floor so that we could get the fire rating, but we kept the ceilings all exposed. The timber that we took out we used to make the bed frames. And so a lot of that was sort of before people were talking about sustainable design and reusing materials, so we were kind of at the right place at the right time. And all the decisions that the owners and all the designers that worked on the project, were the right decisions. And I think it continues, like all good places, when they’re successful and they continue to be relevant, then you kind of know that you did the right thing.

SSR: Yeah, a hundred percent. It was on our cover for a redesign. It means a lot to me too, because we had just done a redesign of the magazine in September of 2012, and it was on our cover.

MA: Yeah, that was a great moment for us as well.

SSR: Yeah. Besides hospitality, you do a ton of residential and multifamily. And I totally agree with you, I think residential feeds hospitality and vice versa. How do you handle those two disciplines in your office? And do you let those teams bleed into each other to riff ideas off each other?

MA: Yeah. I think that where we’re seeing the most overlap is on the residential side in the amenities, because they’re trying to make those amenities more spa-like or hospitality-like. And so you’re seeing things like saunas or steam rooms or treatment rooms, but also maker spaces and lounges that would feel more hospitality-like. And so we’re seeing that. And the bleeding of all those spaces together.

And in terms of the teams, our teams kind of go back and forth across the different typologies, and so that’s where it’s coming in. But Becca Roderick, who heads up our interiors group, comes from a hospitality background. And so she’s kind of abusing that, just because it’s in our DNA, into all the projects.

The Wythe hotel in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York; photo courtesy of MA

SSR: Yeah. No, that’s great. And I think it’s awesome because they can take lessons learned from one to the other, and really inform each other. Is there one project that you have on the boards that you’re really excited about?

MA: Oh, that’s so unfair.

SSR: Pick your favorite child. You can do it.

MA: My favorite project is the one I’m working on. But that being the case, we are doing a project now. We just started, and it’s super exciting for a number of reasons. It’s additional rooms at the Swan Hotel in Disney.

SSR: That’s cool.

MA: Super cool, because it was intimidating or scary because the Swan and the Dolphin by Michael Graves, super iconic buildings. And I was just down there with the team, and it still works. I think there’s a sense of fantasy and all the things you would associate with Disney, but they really work. And over the last however many, I think it’s like 30 years or something, they’ve been upgraded and changed, but they’re still pretty powerful and bold buildings. So in that sense, it’s a little intimidating to actually add another structure in there and just the whole postmodern thing. But I think we have a really, really great scheme, and we’re going to be presenting it to our client, Tishman, and then to Disney. So I’m super excited because I think it will be an iconic building. It plays really nicely with the existing buildings, but it feels like it still works for today. So it’s kind of like, I don’t know, it’s the right context for… We’re doing the right thing for the context.

SSR: Yeah. I’m excited to see what that turns out to be, because I feel like there’s a little stretch for you guys, but a good stretch, right?

MA: Yeah. I mean, kind of going back to the Rossi influence and that whole thing, was like, “Okay, do I really want to do this?” And again, we’ve got some sketches pinned up on the wall and everybody’s like, “Oh, that’s really great.” So I think it’s going to be another one of those iconic projects, like the Wythe or the Samsung building that we did, or Fourth. So we’re super excited about it.

SSR: Are you a Disney guy? Have you been?

MA: Yeah. I mean, my kids are older, but I have been a couple of times and it was great. But I just sit down there and just walking around, it’s like having flashbacks to driving around on a Segway.

SSR: Are either of your kids following you in your footsteps as an architect?

MA: Actually, one of them is, which was kind of surprising. He was working… Well, he got the job. I mean, I had introduced him to an artist and he was working with an artist for a while after school and during the summers. And I thought he was kind of on that track, like wanted to be an artist. And he went to the pre-college program at RISD two summers ago, and he was going to do drawing or something. And I was like, “Great.” And then a week before, and he goes, “I’m changing my major.” And I’m like, “Okay. Can you do that?” He said, “Yes. I’m going to do architecture.” It’s like, “Whoa. Okay.” So yes, he’s at Tulane, he’s a freshman, and he’s studying architecture. I mean, he’s always a really good draftsman person, but it looks like he’s making things out of hemp concrete and stuff like that. So let’s see what happens.

SSR: See where it goes. See where it goes. You mentioned sustainability. I know that’s important to your ethos and your practice. Tell me how do you constantly kind of push that envelope when you’re building these buildings with clients, especially the ones that have greater impact, right?

MA: Yeah. I think it’s always a challenge. And I was interested in sustainable design when I started in college, and there was a book called Design with Climate, which I felt was a really important moment for me to kind of look at that. And also, I did my thesis on New Orleans housing types, and just looking at how buildings were built historically, before air conditioning. Buildings had taller ceilings or they had spaces designed to let airflow below them, or they were raised because they were in a floodplain. And all of those things are things that are still relevant today, even though they were a long time ago. And so those are the kinds of things that I think are important.

I don’t feel like sustainability should be the design statement. I don’t think we should be building buildings that scream like I’m sustainable. I think buildings need to be sustainable, and we need to use sustainable practices and materials using recycled or reclaimed materials. We did a building over 10 years ago, a platinum LEED certified building at NYU, and we used brick that was made from recycled industrial waste, but you would never know that by looking at the brick. So I think it’s important, but it shouldn’t be like the driving visual cue about why a project. That’s just my personal opinion. There are others that feel like that’s, let’s put a big solar panel in front of the building. I think that those should be incorporated in a way that doesn’t dictate a form.

The two-towered Huron luxury condo building in New York; photo by David Mitchell

SSR: Right. No. Just be sustainable, right? Don’t have to shout it. Makes sense. Makes sense. All right. So you travel a ton. What has been a very memorable hospitality experience that might have changed or affected you in a positive way?

MA: I would say staying in a ryokan in Japan. For first, it’s a whole host of reasons, but first of all, most amazing stay in Kyoto, and just seeing that historic architecture. And then also the flexibility of a room. You could stay in a room to sleep or you could stay in there to have a tea, you can invite people in. And just this idea that the space was not specific to a function, but was specific to coming together or being alone. And so I think that that was, for me, was a change. And then, yeah, it was just celebration of travel and the celebration of understanding a culture and being in a place that had been around for hundreds of years, but was still relevant to how we travel and how we experience new things in the world.

SSR: How do you constantly stay inspired?

MA: I would say the single most important thing for me is just being on the street and just walking around, but really going to art shows. And I see every weekend I’m either at galleries or museums, or listening to music, going to shows. But I think just being stimulated by what we see. And New York is an amazing place to do that, but I think wherever I go, I’m trying to sponge and extract inspiration.

SSR: Yeah. And do you encourage your team, too, to put the phone down and look up?

MA: Absolutely. Absolutely. We have a program here, which we… Well, we have an art program, so we invite artists in. We did a collaboration with Proxico, which is a New York-based gallery that really features Latin artists. And so we had an artist takeover, so they took over our space and turned it into a demolition company. So it was like all of the walls and all the exhibition was geared towards that. But trying to have those internal art shows to keep the office fresh and to keep people thinking about inspiration. And then we have openings, which brings people together. And then a lot of times we’ll do a seminar or a talk around the art. So it starts here. We also have something called Beautiful Spaces, where we go out into the world, we look at other projects, we go to showrooms. And so that really stimulates people to experience influences together.

SSR: What is your favorite part of the process?

MA: My favorite part is the eureka moment. There’s always a lot of friction, let’s call it. Trying to absorb the information about what we’re doing in the project, doing research about either similar projects or the neighborhood, or who’s going to be going there, or what we’re going to do, or researching the program. All of that is kind of, I don’t want to say it’s a regular part of the project, but it’s one that’s relatively, let’s call it straightforward. But going from that to the moment where the idea clicks and you say, I got it.

And so that moment, and I don’t know how or when or how it happens, but usually I’m always, for me, I’m tortured. Whether I wake up in the middle of the night, going like, “What? What are we going to do?” “Oh, we’re never going to find a solution for this,” or, “We can’t do that again.”

SSR: I mean, that must be the hardest thing, right? Is like, you’re like, I can’t just do it on that building again.

MA: Right. And so just that moment where it’s just all the clarity. And it’s not like you’re just exercising, exercising, exercising, and then you get to a point, because you never know when that’s going to happen. But it’s like there’s like a parting and an opening up and a clear moment when you say, now it’s right.

SSR: Right. Yeah. Is there still a project on your bucket list?

MA: Yeah, I would say. I’ve done some small galleries and exhibition designs, but I think a museum would be an amazing project. And I think the museum world is going through a lot of change. I mean, the whole world is going through a lot of change, but just in terms of-

SSR: That’s a whole other podcast.

MA: Yeah. We won’t go there. But what museums are and how they function and how we can create a place that is a repository but is also a catalyst for bigger discussions or interactions or meetings or encounters, I think would be a great thing to do.

SSR: Yeah. All right. Well, I hate to end the conversation, but for the sake of time, we always end with the question that is the title of the podcast. So what has been your greatest lesson learned or lessons learned along the way?

MA: I’ve always been a proponent of treating people with respect and in the right way. This sounds hokey coming from an architect, but there’s been so many instances where somebody that I work with, that was a junior person or an intern and now is running the department of a company. And for me to have always been a good person and been treating people with respect and has come back many times in a way that has benefited the firm. But it’s not like I’m not doing it because of that, but I think it’s the right thing to do and it has the additional benefit of paying back in some way.

SSR: That’s awesome. Well, thank you so much. It’s always so good to catch up with you.

MA: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure. Really exciting. Thank you.