Design for Living

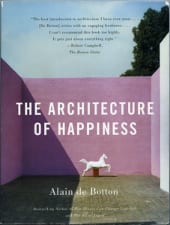

The works of Switzerland-born, London-based writer and philosopher Alain de Botton span novels, literary criticism, and meditations on religion, travel, and work. It was Clodagh’s particular admiration for his 2006 book The Architecture of Happiness that prompted her to contact him for this interview.

The works of Switzerland-born, London-based writer and philosopher Alain de Botton span novels, literary criticism, and meditations on religion, travel, and work. It was Clodagh’s particular admiration for his 2006 book The Architecture of Happiness that prompted her to contact him for this interview.

Tell us about your latest venture, Living Architecture.

Judging from the success of interior design magazines and property shows, you might think that the United Kingdom was now as comfortable with good contemporary architecture as it is with non-native food or music.

;

But scratch beneath the metropolitan, London-centric focus, and you quickly discover that Britain remains a country deeply in love with the old and terrified of the new. Country hotels compete among themselves to tell us how ancient they are; holiday cottages vaunt that they were already in existence when Jane Austen was a girl. The draughty sash window shows no signs of retiring. Inheriting furniture and not bothering with plumbing continue to function as mysterious symbols of status.

A few years ago, I wrote a book about architecture [The Architecture of Happiness] critical of British nostalgia and low expectations. It got a healthy amount of attention, on the back of which I was invited to a stream of conferences about the future of architecture. But one night, returning from one such conference in Bristol, I had a dark moment of the soul. I realized that however pleasing it is to write a book about an issue one feels passionately about, the truth is that-a few exceptions aside-books don’t change anything. I realized that if I cared so much about architecture, writing was just a coward’s way out; the real challenge was to build.

A few years ago, I wrote a book about architecture [The Architecture of Happiness] critical of British nostalgia and low expectations. It got a healthy amount of attention, on the back of which I was invited to a stream of conferences about the future of architecture. But one night, returning from one such conference in Bristol, I had a dark moment of the soul. I realized that however pleasing it is to write a book about an issue one feels passionately about, the truth is that-a few exceptions aside-books don’t change anything. I realized that if I cared so much about architecture, writing was just a coward’s way out; the real challenge was to build.

So on the back of a notepad was born a project which officially launched two years ago: Living Architecture is a not-for-profit organization that puts up houses around the UK designed by some of the world’s top architects and makes these available to the public to rent for holidays throughout the year.

Living Architecture: Balancing Barn

Our dream was to allow people to experience what it is like to live and sleep in a space designed by an outstanding architectural practice. While there are examples of great modern buildings in Britain, they tend to be in places that one passes through (airports, museums, offices), and the few modern houses that exist are almost all in private hands and cannot be visited. This seriously skews discussions of architecture. When people declare that they hate modern buildings they are on the whole speaking not from experience of homes, but from a distaste of post-war tower blocks or bland air-conditioned offices.

Living Architecture: Balancing Barn

Living Architecture’s houses are deliberately varied. One of them by the Dutch firm MVRDV hangs precariously off the edge of a hill in Suffolk. Another in Thorpeness by the Norwegian architects JVA has four steel roofs, each of which houses a bedroom and a bathroom. A third, by the young Scottish practice NORD, is a stark black box in the shadow of Dungeness nuclear power station. A fourth, by the legendary Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, is a secular mini-monastery which aims to bring an ecclesiastical calm and solemnity to the Devon countryside.

The idea has been to avoid the obvious and to place houses in locations one hadn’t necessarily ever thought of holidaying in and to design rooms different from those that people know from their own homes. We also want to keep things accessible. Prices start at twenty pounds per person per night and the buildings themselves, while always comfortable, are far from grand.

Living Architecture: Balancing Barn

The organization has an educational mission at its core, a wish to teach as well as to soothe and relax; that there are luxurious toiletries in the bathrooms is just a way of sweetening the pill of learning.

For a writer, it was undeniably something of a challenge to have to become a practical sort of person. Behind every house lies a seemingly endless procession of meetings with donors, local authorities, architects, waste disposal experts, and cutlery manufacturers. The house rental business demands a keen attention to detail: you won’t get far without an in-depth knowledge of mattress protectors and the best dog policy (yes, but not in the bedrooms). Yet there’s fun in the minutiae. Whatever the pleasures of designing your own home, it’s perhaps even more satisfying imagining someone else’s holiday needs, to design their bedside library, welcome basket, and closet.

Living Architecture: Dune House

I wouldn’t have driven this project forward if I didn’t believe that architecture changes our characters. We are simply not the same people in whatever room we are in. For too long in Britain, our buildings have suggested that the past is the only worthy realm, that we have to dress in the clothes of yesteryear, and that technology is bad and the future terrifying. Living Architecture’s houses propose a new vision of the United Kingdom as a country that is reconciled to technology, that is no longer painfully in thrall to the past, that is democratic, tolerant, playful, and optimistic.

The salvation of British housing lies in raising standards of taste. If one considers how rapidly and overwhelmingly this has been achieved in cooking, there is much to be optimistic about. Consumers have learnt to ask probing questions about salt or fat levels which it wouldn’t have occurred to a previous generation to raise. With the right guidance, a similar sensitivity could rapidly be fashioned to the worst features of domestic buildings. My hope is that a holiday in a Living Architecture house will, in a modest but determined way, help to change the debate about what sort of houses we want to live in.

Living Architecture: Dune House

And the School of Life?

One of the paradoxes of modern consumer society is that while

you can find thousands of stylish businesses that will sell you the

perfect coffee or jumper, disappointingly few enterprises are interested

in serving up anything that could benefit your mind. A Londoner keen to

take in some ideas in an attractive and lively setting has a serious

shortage of options to hand. Most education open to the general public

takes place in gloomy lino-floored institutions, under the auspices of

people who remind us of why academic is also a synonym for remote and

boring, and why we were once probably quite glad to quit school or

college.

Living Architecture: Dune House

That’s why, a few years ago, some friends and I came together to

start an educational establishment with a difference. For a start, the

School of Life has a passionate belief in

making learning relevant-and so runs courses in the important questions

of everyday life. Whereas most colleges and universities chop up

learning into abstract categories (‘agrarian history,”the 18th century

English novel’), the School of Life titles its courses according to

things we all tend to care about: careers, relationships, politics,

travels, families. An evening or weekend in one of its courses is likely

to be spent reflecting on such matters as your moral responsibilities

to an ex partner or how to resolve a career crisis.

Living Architecture: Shingle House (photography by Charles Hocea)

The School has a division offering psychotherapy for

individuals, couples, or families-and it does so in a completely

stigma-free way. For the normally reserved British, it must be a first

to have an institution that offers therapy from an ordinary high street

location and moreover, treats the idea of having therapy as no more or

less strange than having a haircut or pedicure, and perhaps a good deal

more useful.

In a culture where anyone who attempts a serious conversation is

at once accused of belonging to the ‘chattering classes,’and where

anything too intellectual is in danger of being called pretentious, the

School of Life attempts to put learning and ideas back to where they

should always have been-right in the middle of our lives.

Have you visited the Commune by the Great Wall in China or Hotel

Puerta America in Madrid? If so did they at all serve as inspiration

for this project?

I haven’t visited either of them, but they sound like

fascinating projects, trying to make great architecture available to

people who might not otherwise be able to afford it.

I loved your pop-up boat hotel on the Thames. I hear that you

have plans to move the boat throughout London in coming years. How do

you go about choosing sites?

www.aroomforlondon.co.uk was at origin part of the Cultural

Olympics, which ran alongside the main 2012 Olympics in London. The

thought was to create an innovative one-bedroom hotel perched on the

edge of the River Thames. It has been such a success that it will be

kept on for 2013, too, so anyone visiting the capital should be sure to

book a night there.

Speaking of London, what do you feel is the lasting legacy of the London Olympics in terms of impact on communities?

The Olympics has hugely boosted confidence in the UK and shown

the world what an innovative, daring, creative, and nicely mad people we

are.

How do you plan to grow your concept of accessible modern

design? While the homes you have available are gorgeous and inspiring,

they come with a hefty price tag to build. How does the average citizen,

earning a modest income, translate these concepts into reality? Can I

design one for you?

We will in the coming years start to build whole communities of

accessible affordable housing, designed by top architects. It’s taking

time, but that’s the goal. We are democratic and egalitarian to the core

with this project.

With your brains and talent, you could make a huge impact

rallying architects and designers in a charitable way for refugee homes

in places such as Haiti. And it’s a great opportunity to bring great

exposure to affordable modern design. Ever consider taking on an

endeavor of this nature? I would volunteer,

I never say no to anything. Sure, why not give it a go?

It is uncommon in modern society to see someone sitting on a bus

or subway and simply thinking, and not playing with a gadget. Are we

losing the ability to contemplate?

One of the dreams of what a public space should be like comes to

us from ancient Athens. From what we can gather, Athenians liked the

concept that public space should be just that: space where members of

the public could meet one another, exchange ideas, do business, buy a

chicken or a loaf of bread, and have a natter, as humans like to do.

The dream of Athens has resided down the ages, so much so that

when we contemplate our own public spaces, we get rightly worried by the

lack of public interaction in them: we go shopping, but we don’t talk

to anyone. We crowd together but we don’t get to know each other. We

look into one another’s eyes, but our minds are elsewhere. We are

together, but very much apart.

The anonymity of modern public space is all the more insulting

because the possibility of closeness and dialogue is apparently so near.

It’s particularly weird for two people to ignore one another when they

are sharing the same park bench or railway banquette. Alienation is

thrown into relief by the simultaneous presence of proximity and

distance. This is where the contemporary addiction to mobile devices

comes in. They enrage and puzzle us because they make concrete just how

unable we’ve become to connect with our fellow humans. We laugh at

ourselves holding these machines, as we might whenever a guilty secret

has been exposed.

More paradoxically still, these machines show us that we do want

to connect with humans, but very much on our own terms: through

language but not voice, through a blog entry or a tweet, not an ongoing

dialogue. We crave others, but others who’ve been silenced and

compressed and made palatable by the magicians of data. The raw,

uncurated encounter with another human is what’s become so problematic.

You have said that, “Heartache may be bad for the soul, but it’s

great for bookshops.” Why do we often find happiness via pieces of art

that convey sadness?

Given how much time we spend being sad, it’s surprising to

recognize that we may actually not be very good at sorrow. There are

better and worse ways to be distressed. One of the unexpectedly

important things that art can do for us is teach us how to grow more

adept at suffering.

Consider Richard Serra’s sculpture, ‘Fernando Pessoa.’It is

encouraging an engagement with sadness. It is taking us in a very

unusual direction. The outward chatter of friendship in society is

typically cheerful and upbeat. Confess a problem to someone and they

tend at once to look for a solution and point us in a brighter

direction.

Richard Serra’s “Fernando Pessoa”

Richard Serra’s work does not deny our troubles. It doesn’t tell

us to ‘cheer up.’It tells us that sorrow is to be expected. The large

scale and overtly monumental character of the work constitute a

declaration of the normality of sorrow. Just as Nelson’s Column, in the

center, of Trafalgar Square, is confident that we will admit the

importance of naval heroism, so Serra’s ‘Fernando Pessoa'(2007-08,

named after a Portuguese poet who knew about sorrow: ‘Oh salty sea, how

much of your salt / is tears from Portugal’) is confident that we will

all recognize and respond to somber and solemn emotions. Rather than be

alone with such moods, the work proclaims them as central and universal

features of life.

Moreover, Serra’s work places sorrow before us in a dignified

way. The work does not go into details; it does not analyze any

particular cause of suffering. Instead it presents sadness in general as

a grand, ubiquitous emotion. In effect, it says: ‘When you feel sad you

are participating in a venerable experience -to which I, this

monument-am dedicated; your sense of loss and disappointment, of

frustrated hopes and grief at your own inadequacy, elevate you to

serious company. Do not ignore or throw away your grief.’

We can see a great deal of artistic achievement as ‘sublimated’

sorrow on the part of the artist, and in turn, in its reception, on the

part of the audience. The term ‘sublimation’derives from chemistry. It

names the process in which a solid substance is directly transformed

into a gas, without first becoming liquid. In art, ‘sublimation’refers

to the psychological processes of transformation, in which base and

unimpressive experiences are converted into something noble and fine,

just what may happen when sorrow meets art.

Many sad things become worse because we feel that we are alone

in suffering them. We experience our trouble as a curse or as revealing

our wicked, depraved character. So our suffering has no dignity: it

simply seems what is due to our freakish nature. We need help in finding

dignity and honor in some of our worst experiences, and art is there to

lend them a social expression.

You have said that our travel experience is somewhat dictated by

who we are with. Is it easier to find enjoyment solo? And in a larger

context, is it easier in life to provide your own happiness?

For most of us, when we think of how to be happy, we think of

one (or all of) three things: falling in love, finding satisfaction at

work, and going traveling. Traveling can form some of our greatest

fantasies: we lie in bed reading a travel supplement, looking at

pictures of faraway places (London/Honolulu/Paris/Naples/Sydney/Bali)

and think, ‘Here I could be happy!’

But the reality of travel seldom matches our daydreams. The

tragi-comic disappointments are well-known: the disorientation, the

mid-afternoon despair, the lethargy before ancient ruins. And yet the

reasons behind such disappointments are rarely explored. We are

inundated with advice on where to travel to; we hear little of why we

should go and how we could be more fulfilled doing so.

My book, The Art of Travel, is an attempt to tackle the curious

business of travelling – why do we do it? What are we trying to get out

of it? In a series of essays, I write about airports, landscapes,

museums, holiday romances, photographs, exotic carpets, and the contents

of hotel mini-bars. I mix my own thoughts about travel with those of

some great figures of the past: Edward Hopper, Baudelaire, Wordsworth,

Van Gogh, and Ruskin among them. The result is a work which, unlike

existing guidebooks on travel, actually asks what the point of travel

might be, and modestly suggests how we could learn to be happier on our

journeys.

I enjoy transient places like airports and train stations. Do you have a favorite transit downtime activity?

When feeling sad at home, I have often boarded a train or

airport bus and gone to Heathrow where, from an observation gallery in

Terminal 2, or from the top floor of the Renaissance Hotel along the

north runway, I have drawn comfort from the sight of the ceaseless

landing and take-off of aircraft.

I have long been attracted to traveling places: to service

stations and motels, airports and train stations, harbors and diners-perhaps because, in spite of their architectural limitations and

discomforts, in spite of their garish colors and harsh lighting, these

melancholy places seem to offer an escape from habit and the false

fellowship of ordinary life.

From a car park beside O9L/27R, as Heathrow’s north runway is

known to pilots, the 747 appears at first as a small, brilliant white

light, a star dropping towards Earth. It has been in the air for twelve

hours. It took off from Singapore at dawn. It flew over the Bay of

Bengal, Delhi, the Afghan desert, and the Caspian Sea. It traced a

course over Romania, the Czech Republic, southern Germany, and began its

descent, so gently that few passengers would have noticed a change of

tone in the engines, above the gray-brown, turbulent waters off the

Dutch coast. It followed the Thames over London, turned north near

Hammersmith (where the flaps began to unfold), pivoted over Uxbridge,

and straightened course over Slough. From the ground, the white light

gradually takes shape as a vast two-storied body with four engines

suspended like earrings beneath implausibly long wings. In the light

rain, clouds of water form a veil behind the plane on its matronly

progress towards the airfield. Beneath it are the suburbs of Slough. It

is three in the afternoon. In detached villas, kettles are being filled.

A television is on in a living room with the sound switched off. Green

and red shadows move silently across walls; the everyday. And above

Slough is a plane that a few hours ago was flying over the Afghan

desert. Slough-Afghanistan: the plane a symbol of worldliness, carrying

within itself a trace of all the lands it has crossed, its eternal

mobility offering an imaginative counterweight to feelings of stagnation

and confinement.

Nowhere is the appeal of airports more concentrated than in the

television screens which hang in rows from terminal ceilings announcing

the departure and arrival of flights and whose absence of aesthetic

self-consciousness, whose workmanlike casing and pedestrian typefaces do

nothing to disguise their emotional charge nor imaginative appeal.

Tokyo, Amsterdam, Istanbul. Warsaw, Seattle, Rio. The screens bear all

the poetic resonance of the last line of James Joyce’s Ulysses: at once a

record of where the novel was written and, no less importantly, a

symbol of the cosmopolitan spirit behind its composition: ‘Trieste,

Zurich, Paris.’The constant calls of the screens, some accompanied by

the impatient pulsing of a cursor, suggest with what ease our seemingly

entrenched lives might be altered, were we to walk down a corridor and

on to a craft that in a few hours would land us in a place of which we

had no memories and where no one knew our names. How pleasant to hold in

mind, through the crevasses of our moods, at three in the afternoon

when lassitude and despair threaten, that there is always a plane taking

off for somewhere else.

Traveling places are also valuable sanctuaries when one is

feeling lonely. I remember driving out to a service station on the road

between London and Manchester on a bleak December day. There was, apart

from the motorway, no road linking this service station to other places,

no footpath even, it seemed not to belong to the city, nor to the

country either, but to some third, travelers’realm, like a lighthouse

on the edge of the ocean. The geographical isolation enforced the

atmosphere of solitude in the dining area. The lighting was unforgiving,

bringing out pallor and blemishes. The chairs and seats, painted in

childishly bright colors, had the strained jollity of a fake smile. None

of the other people in the station were talking, no one was admitting

to curiosity or fellow feeling. We gazed blankly past one another at the

serving counter or out into the darkness. We might have been seated

among rocks.

I sat in one corner, eating fingers of chocolate and taking

occasional sips of orange juice. I felt lonely but, for once, this was a

gentle, even pleasant kind of loneliness because, rather than unfolding

against a backdrop of laughter and fellowship, in which I would suffer

from a contrast between my mood and the environment, this loneliness

unfolded in a place where everyone was a stranger, where the

difficulties of communication and the frustrated longing for love seemed

to be acknowledged and brutally celebrated by the architecture and

lighting.

The loneliness brought to mind certain canvases by Edward

Hopper, which, despite the bleakness they depicted, were not themselves

bleak to look at, but rather allowed their viewers to witness an echo of

their own grief and thereby feel less personally persecuted and beset

by it. It is perhaps sad books that console us most when we are sad, and

to lonely traveling places that we should drive when there is no one

to hold or love.

Is it still possible to find life changing or defining moments

through art forms like books and music when they have become

increasingly things that our society expects for free via downloading,

etc ?

As an artist, I deeply resent the assumption that our work

should be ‘free’. Only if it was free to make should it be free to

acquire.

Can things like a well-designed piece of furniture really make us happy?

Beauty has a huge role to play in altering our mood. When we

call a chair or a house beautiful, really what we’re saying is that we

like the way of life it’s suggesting to us. It has an attitude we’re

attracted to: if it was magically turned into a person, we’d like who it

was. It would be convenient if we could remain in much the same mood

wherever we happened to be, in a cheap motel or a palace (think of how

much money we’d save on redecorating our houses), but unfortunately

we’re highly vulnerable to the coded messages that emanate from our

surroundings. This helps to explain our passionate feelings towards

matters of architecture and home decoration: these things help to decide

who we are.

Of course, architecture can’t, on its own, always make us into

contented people. Witness the dissatisfactions that can unfold even in

idyllic surroundings. One might say that architecture suggests a mood to

us, which we may be too internally troubled to be able to take up. Its

effectiveness could be compared to the weather: a fine day can

substantially change our state of mind – and people may be willing to

make great sacrifices to be nearer a sunny climate. Then again, under

the weight of sufficient problems (romantic or professional confusions,

for example), no amount of blue sky, and not even the greatest building,

will be able to make us smile. Hence the difficulty of trying to raise

architecture into a political priority: it has none of the unambiguous

advantages of clean drinking water or a safe food supply. And yet it

remains vital.

You ask many questions in your book Religion for Atheists. Is a religious society a happier society?

In my book, I argue that believing in God is, for me as for many

others, simply not possible. At the same time, I want to suggest that

if you remove this belief, there are particular dangers that open up. We

don’t need to fall into these dangers, but they are there and we should

be aware of them. For a start, there is the danger of individualism: of

placing the human being at the center stage of everything. Secondly,

there is the danger of technological perfectionism, of believing that

science and technology can overcome all human problems, that it is just a

matter of time before scientists have cured us of the human condition.

Thirdly, without God, it is easier to lose perspective, to see our own

times as everything, to forget the brevity of the present moment and to

cease to appreciate (in a good way) the miniscule nature of our own

achievements. And lastly, without God, there can be a danger that the

need for empathy and ethical behavior can be overlooked.

Now, it is important to stress that it is quite possible to

believe in nothing and remember all these vital lessons (just as one can

be a deep believer and a monster). I simply want to draw attention to

some of the gaps, some of what is missing, when we dismiss God too

brusquely. By all means, we can dismiss him, but with great sympathy,

nostalgia, care, and thought.