Meeting of the Minds

David Rockwell in conversation with Peter Gelb, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera.

Rockwell and Gelb photo by Jeffrey Mosler

Rockwell and Gelb photo by Jeffrey Mosler

DR: I wanted to talk about transformation, which, in the world of

architecture and restaurants and hotels, is more of a subtext, but my

contention is equally relevant. I thought focusing on transformation was

interesting-particularly in a world where software matters more and

things change quickly. My earliest memories of New York were theater and

restaurants, places that create a deep experience.

PG: You certainly have been responsible for transforming the restaurant experience in a huge way.

DR: I think architects place such a premium on permanence, but in

fact, nothing is really permanent. In hospitality, there’s an overlap.

I’m wondering, as someone who is acknowledged for bringing

transformation to the Met, do you think that’s critical to keeping the

Met relevant?

PG: Well, any business, and any art form that’s been around a

long time, has to go through an ever-changing process. It has to be

constantly transforming itself if it wants to survive. And even

businesses that think that everything is okay, find out in a very

unexpected and unpleasant way, that it’s not. So, coasting doesn’t work

in any form of life. Unless it’s downhill skiing. I was appointed to run

the Met partly because I had not run another opera house, and because

the members of the board who chose me realized a change was absolutely

necessary. They didn’t quite understand what kind of transformation it

would be, but they knew they were losing their audience.

DR: As long as you don’t change what people don’t want changed.

PG: People don’t always know what they want or don’t want

changed. There’s a kind of knee-jerk [reaction] amongst an older

audience that change is something to be very afraid of. But, numbers

don’t lie, and the Met is losing its audience. It’s getting older and

smaller. The question is whether it would be a change that would be

successful or not. And part of the problem in that phase is that,

because it had been successfully coasting, at least theatrically, for so

many years, change then seems more dramatic and potentially more

damaging to those who don’t want change.

DR: I hadn’t really thought of this before, but I know a little

bit about how far ahead it takes to put on a production. So, change or

transformation at the Met has to, by definition, happen over a very

extended period of time, just because of the time it takes to get things

into production.

PG: Absolutely. I knew that I couldn’t wait three or four years.

Operas, as you point out, are planned so far ahead, I did not have the

luxury to wait until the cycle that had been planned to play out. So I

immediately jumpstarted a number of productions, in a way that typically

is not done in the opera world. My first opening night as general

manager was [film director] Anthony Minghella’s Madame Butterfly. And that sent a signal that the Met was looking at things differently, aesthetically.

Siviglia, designed by Michael Yeargan. (Photo by Ken Howard,

Metropolitan Opera)

DR: And it happened to be a huge win.

PG: It was a huge win, and as a producer, you know and I know,

things can always look great on paper. But you never know until the

curtain goes up and then comes down at the end of an evening whether you

really have a success or not. So, we were very fortunate in that most

of the new productions that were put on the stage in the first couple of

years of my tenure were successful, and did make an impression on the

public in a positive way. At the same time, we were changing things by

inviting top stage directors who had never worked here before because

opera is one of the most complicated, if not the most complicated,

performing art forms. It’s not just a huge theater and a stage that has

to be filled with scenery. It has to work with an orchestra and a cast

of very fragile opera singers.

DR: Many of whom, I assume, resist any kind of transformation.

PG: What’s fortunate is that there’s a whole new generation of

opera singers who believe that acting is important and that full

representation of your characters, through the singing and the acting of

a role, is what makes the performance. They are also very fragile. They

have to get on the stage in front of 4,000 people and not crack their

high notes.

DR: So it’s artist and athlete.

PG: It’s the most athletic and exciting and thrilling of the

performing arts for that reason. Because the public comes to hear these

singers. Not just for the interpretation, but also to see if they’ve

made it.

DR: Someone else who’s contributing to this issue is Richard

Wurman, who founded the TED conference. The first time I was invited to

speak at TED, Richard made it clear that he wanted people who were

talking about things they were amateurs at, in the best sense-things you

were passionate about. Do you feel like part of the benefit you’ve had

in creating a transformation at the Met is coming to it with an

outsider’s eye?

PG: Yes and no. I think I have an outsider’s eye in the sense

that I’m not an East Side opera nut. A lot of the people who end up in

administrative positions in opera houses are former musicians or

singers. And, very often they are so fanatical themselves that they

don’t have a proper sense of perspective. On the other hand, I’ve worked

with opera singers, and even though I haven’t run an opera house, I’ve

worked as a producer, worked with talent in this field, and loved opera

all my life. I’m coming to it with a healthy sense of perspective, I

think, but certainly, a very developed sense of what to do as a

producer. Because of my background in the media, I have been able to

emphasize the theatrical side of opera, which is essential for it to

continue, but also the ability to bring opera to a larger public and to

strip away all the layers of dust.

DR: To see [movie] marquees that feature operas in the Met is just thrilling.

PG: Yes. We just added Russia, China, and Israel. We have 50

countries that are taking our live, high-definition transmissions into

movie theaters; 1,600 movie theaters on six continents. And that has

created a whole new surge of interest in the opera experience. What’s

remarkable is the Met is one of the biggest opera audiences in the house

itself-about 850,000 people a year. That only represents 20 percent of

our paying audience. Eighty percent of our audience is seeing the Met in

arts centers and theaters in other countries.

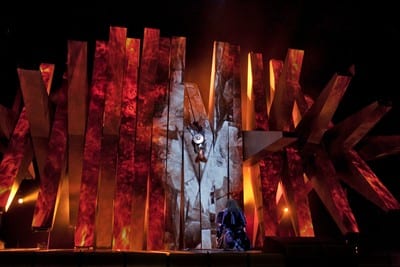

The Act 3 finale of Wagner’s Die Walküre, directed and designed by Robert Lepage. (Photo by Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera)

DR: Same with the NFL. That’s something like 93 percent.

PG: This process began sort of using sports as a model. Because I

wanted to kind of strengthen the bond between the opera fanatics and

the opera house, by making the content available all the time, in every

possible platform. We started a Sirius/XM radio station. We have our own

channel, where we have live audio feeds three or four times a week,

plus we archive operas the rest of the time; we have them streaming on

our website. We have every live show we do at the movie theaters, that

has a secondary life in television, and, on a subscription opera channel

service, we have a pay service. It’s transformed the relationship

between our company and our public. It also changed the relationship

between the performers and the public. And it helped in our casting,

because I’m able to get all the top stars who want to sing here more

often than ever before, because of the visibility. Anna Netrebko, the

reigning Russian soprano star who opens our season in Anna Bolena,

knows that two weeks later, she’s going to be in a matinee and open our

high-definition season. And she’ll be seen by a quarter of a million

people, everywhere from Moscow to Morocco to Miami, in a giant movie

screen, live.

DR: You mentioned that you’ve always loved the performing arts.

When you were young, were there experiences you had that fostered your

interest?

PG: Sure. I had great experiences because my parents were very

swept up in the cultural scene in New York. My father, at the time I was

a little boy, was the No. 2 drama critic at the [New York]

Times. He went on to become the managing editor. He and my mother used

to take me to the theater all the time. I remember seeing Hamlet when I was five years old. And when I was a teenager, I actually worked here as an usher.

DR: Do you remember who played Hamlet?

PG: Donald Madden, who died a couple of years ago. That’s a

performance I remember, as well as some performances I’ve seen just a

few months ago. My father was very good friends with [Public Theater

Founder] Joe Papp, and I remember being taken to the early versions of

Shakespeare in the Park, even before they built the Delacorte Theater.

So I have great memories of the theater.

DR: There’s a lot of interesting work done in technology and

architecture. And you’ve really embraced technology. Are there pros and

cons?

PG: Any artist [knows that] technology is only as good as the

service in which you place it. And there are some directors and

designers now who have figured out how to use modern technology in their

visual vocabulary and in the service of their storytelling. A perfect

example of that is Robert Lepage [director and designer of the Met’s

current Ring Cycle], who thinks in terms of visual effects going

back to the 16th century, as well as the most modern ones. So he’s

interested in the whole range of everything that’s ever been

accomplished technologically, from the earliest days of theater and

pre-theater, to what has not yet been seen. For example, in the next

installment of the Ring, “Siegfried,” that opens in October, there is a

technology that actually simulates a real 3-D experience. Those planks

[the basis of LePage’s set], when they’re in the right position, with

the right projection on them, are meant to represent the underbelly of

the forest where Siegfried grew up, which is the opening image of the

opera. It’s going to blow the audience away, because you actually see

the snakes slithering and branches moving, and it looks like you’re in a

very real theatrical place that is unlike any place anybody in this

opera has ever seen before.

DR: I’m struck by the mammoth size of your productions and the

fact that there’s a different one every day. Any thoughts about how you

create a system that embraces transformation?

PG: The system that we’ve tried to set up is one in which we have

multiple goals. So, theatrically, it’s a question of breaking new

ground in the service of storytelling. For me, the best told story is

one that works on multiple levels, so that the older opera audience who

knows, say Don Giovanni well, will appreciate a new telling of it.

DR: With very little technology in that case, right?

PG: In the case of our new one, it’s fairly straightforward, but

with a very modern aesthetic sensibility. The way we’re achieving

transformation is through a combination of theatrical innovation, which

embraces technology, and opening the art form up to the widest possible

public. Everything that we do sort of tries to address those goals.

DR: You make all your sets yourselves, right?

PG: Not always. Sometimes they’re made elsewhere. But the Met is a

remarkable center of artisans. You know, we have some of the greatest

scenic painters in the world working here.

DR: I’m impressed by the fact that one day you’ll see this

amazingly crafted, big physical presence, and the next a very sleek

thing.

PG: When the Met was built in 1966, it was the most modern and

technically advanced opera house. Now, 40 years later, it’s in need of

major upgrades. And so we’ve been doing it in a patchwork fashion. In

the period when the Met was built, the acoustical science of building

concert halls and opera houses was not very advanced. And the attempt to

create great acoustical halls, to match the great acoustics of the

halls of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when building materials

were different, resulted in some of the worst acoustically efficient

concert halls and opera houses. The Met, miraculously, somehow escaped

this problem. The difference between an opera house and a concert hall,

of course, is that there’s a fourth acoustical wall, which is the

scenery. So, the scenery has to be built properly in order to complete

the acoustics of an opera house.

DR: Do you have any ability to computer model that for scenic designers?

PG: No. But we just give intuitive advice. We know that scenery

is built out of hard substances, and that singers who are placed in

front of the scenery that fill up a large part of the stage, and who are

in the right position downstage usually sound pretty good. And we know

that not to have wide, open spaces into the wings and upstage.

Avoiding those kinds of things results in better acoustics. This set of

the Ring is acoustically superior. I mean, Jimmy Levine, our music

director, when he first heard the singers on this set, was ecstatic.

Because it’s what every conductor dreams of- having a set which is going

to propel the sound out into the audience.

DR: Any thoughts about transformation at the performer level? I

think it’s fascinating to think about knowing the singers, and then

seeing them take on the role in the physical environment, where the

transformation’s happening from their point of view.

PG: It’s really hard to underestimate how difficult it is for a

singer on the stage of a huge opera house like the Met, where they have

to have a voice that’s big enough to command the space. And the biggest

challenge from a theatrical point of view is to give a dramatic

performance that makes the audience believe the singer is not simply

worrying about their vocal production. So, it’s very rare that you can

find [that kind of] a singer-although, increasingly less so, because of

what singers understand today, and the directors with whom they’re

working. I remember when Minghella worked with the cast of Madame Butterfly

on his first day of rehearsal. He wouldn’t let them sing, which was

unheard of. He had them read the libretto because he wanted them to do

something that singers very rarely do, which is to listen to each other.

The best singers are learning that they have to be able to give a

complete theatrical performance. Deborah Voigt took on the role of

Brünnhilde here in our Ring Cycle. If you were sitting here in the front rows of the audience, or in the back of the house, you had the sense of, here is somebody. She was Brünnhilde.

DR: Do you have a desk in the orchestra?

PG: Because I spend a lot of time there, making sure that the

directors I’ve hired feel good about working here, I’ve sort of moved my

headquarters. It’s not really a desk. The way the Met is set up in

rehearsal modes, we have lots of tech desks. They’re sort of tabletops

that are laid on top of chairs. And we have benches that we put on top

of the arms of chairs so we can raise up. And I have a laptop, a phone,

and I do my business there. At the same time, I can keep an eye on

what’s going on on the stage, and put my two cents in if necessary.

DR: It’s an interesting analogy, though, to other worlds of

technology where there’s a strong curator at the center of the

experience. And being right there allows artists to feel like they can

collaborate in perhaps a different way, and that they’re supported. What

are the parts of the transformation of the Met that haven’t happened

yet that you look forward to, if those exist?

PG: I think there are some parts of the transformation that will

never happen. It will never be possible to replace a large part of the

older musical repertoire with new pieces.

DR: Because of volume or because of love for the old productions?

PG: Because of love and because of the talent. I think that the great, timeless pieces have not been surpassed.

DR: Didn’t you refer to opera as the pop music of its day?

PG: It wasn’t exactly the pop music of its day. But it was much

more popular, that’s for sure. And it certainly had the support of the

entire intellectual creative community in any one country.

DR: Although, who knows? I would imagine, as we look 20, 30 years

out, some of the things you’re doing here will create momentum for new

works.

PG: We’re pushing for new works all the time.

DR: And is the dining experience ever going to mirror what’s happening with the opera?

PG: Well, most interesting restaurants vary their repertoire all the time, don’t they?

DR: Do you feel like the transformation of Lincoln Center has given new energy to the Met?

PG: I’m actually a believer that the energy at Lincoln Center

comes from within the buildings, not the exterior. What gives a theater

or a cultural center like Lincoln Center, or a city like New York, its

sense of dynamism is the individual efforts that go on within the

confines of each institution. It’s like every great restaurant in New

York.

DR: Nothing makes a restaurant design look better than a great chef.

PG: Right.

DR: Well, here’s looking forward to my opportunity to work on this incredible stage.

PG: I look forward to that.